Capital markets firms must do more to protect IP

Capital markets firms are losing their intellectual property too easily to competitors, business partners and third parties. Most companies could benefit from a tougher approach to IP, including licencing agreements and more use of patents, according to a new report by analyst firm Aite.

Intellectual property consists of innovative new ideas, business practices and new technologies. So far, capital markets companies have largely focused on trademarks for benchmarks and indices and trade secrets such as internal software. But they have often left the patents up to the independent software vendors – with serious negative effects for their own business, according to the report, Monetizing Innovation in Capital Markets: An Intellectual Property Primer.

“Capital markets firms place relatively low values on their own internal IP and in many cases have failed to make the most of it,” said David B. Weiss, senior analyst at Aite and author of the report. “Too many firms manage to fall into enormous IP traps, essentially shooting themselves in the foot. The inevitable result is both competitive and economic harm to themselves. It is now incumbent on these firms to value, protect and monetise their IP, treating it as a core asset like any other they maintain.”

Historically, it was more difficult to protect IP in the capital markets because these companies didn’t produce any physical goods, and getting a patent in business processes and software programmes could be a challenge. But mostly the problem appears to stem from a lack of awareness. For example, one of the most straightforward ways for a company to lose IP is if an employee responsible for innovation leaves the company, taking the IP they created with them. Aite notes that often, companies haven’t taken any steps to retain the IP the individual created while under its employ.

Another problem is that through agreements, independent software vendors may obtain proprietary business requirements or functional specifications from the firm. “What starts as a accustom project for a capital markets firm may end up in enhancements to the commercial product they’re paying for and ultimately in the hands of all the other licensees of that product, including their competitors,” warns Aite.

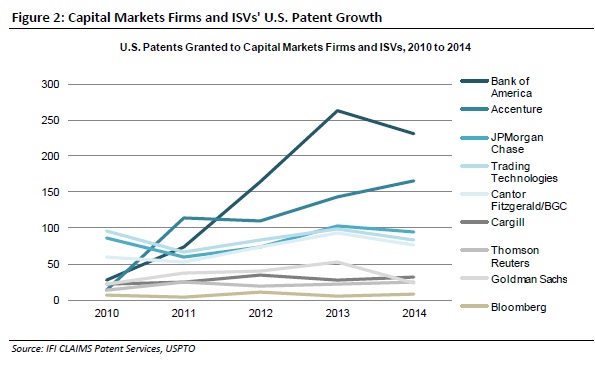

While some of the larger global banks have plenty of patents – Bank of America patented over 200 in 2014 – most others produce far less. The same year, Goldman Sachs patented less than 50. Ironically, markets have been established for IP itself, built on the capital markets model. Cantor Fitzgerald operates an IP auction marketplace, while a number of patent brokers exist including GTT Group, Inflexion Point, Ocean Tomo (owned by ICAP) and Pluritas.

IP can also be converted into cash. Specifically, patents can be cross- licenced, and in a number of industries such as aerospace, this is commonplace. Licencing IP for use by others is a way to bring in revenue. For example, some companies have large patent portfolios that bring in annual licencing revenue of $250 million or more. A few even early billions from their IP.

IP can also be converted into cash. Specifically, patents can be cross- licenced, and in a number of industries such as aerospace, this is commonplace. Licencing IP for use by others is a way to bring in revenue. For example, some companies have large patent portfolios that bring in annual licencing revenue of $250 million or more. A few even early billions from their IP.

Aite makes several recommendations for capital markets firms. Chief among these is to licence their IP, revisiting all relationships with independent software vendors to make sure that these are paying for any IP they receive. They should also licence their patents and trademarks to take advantage of new opportunities and solve problems. For example, each company should focus on what it does well and find partners to do the tasks it doesn’t.

“Firms that hope to reap the benefits of innovation as an IP asset must develop firm-wide IP action plans,” said Weiss. “Such IP action plans include elements of employee engagement, institutionalised innovation in business and technology, IP capture, patent filing and prosecution and IP monetisation.”