Regulations raise new questions about industry standards

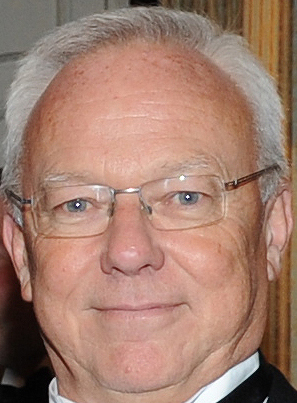

Chris Pickles is an independent fintech consultant and member of the Bloomberg Open Symbology team

Financial market regulations across the globe are increasingly focusing on risk management. This includes ensuring it is clear who firms are trading with and for, and confirming that firms can identify the instruments being traded. As a result, the field of reference data is increasingly held under the regulatory microscope and that lens extends to the standards used to identify financial instruments, writes Chris Pickles.

Enhanced regulatory oversight not only highlights what market participants and regulators already know about standards and their importance to well-functioning financial markets, but also what they don’t know, and one thing’s for certain: in that area, the devil is in the detail.

In the United States, regulators are asking new questions about standards, particularly those used to identify derivatives products and trades and for trade auditing purposes. Meanwhile, the European Securities & Markets Authority is running an industry consultation asking firms which standards they use and how they can help firms achieve compliance more cost-effectively.

To those relatively new to the world of standards, even defining or identifying the true purpose of a standard can get confusing. Is it a data standard, a messaging standard or a business process standard? Is it a standard for making standards? The consultations now ongoing are making firms and regulators re-examine and – in some cases – challenge the assumptions they’ve made about standards, business operations, operational efficiency and compliance.

This is particularly true for instrument identifiers. A huge range of different financial instruments are used across the financial community for an enormously wide variety of purposes. More and more about these instruments now has to be reported to regulators. MiFID I focused on transparency around equities; AIFMD on alternative investment funds; EMIR addressed derivatives and now MiFID II and MiFIR are looking broader still. With regulators themselves now processing and storing information on such a broad and growing range and volume of instruments, new questions are being raised about the data standards used to identify them.

So how many different financial instruments are we talking about? Around the time MiFID I was implemented, the European Central Bank mentioned it had a central database covering over five million financial instruments. At the time, that sum sounded enormous – the kind of coverage you might expect a global data vendor to manage, going far beyond the number of equities and bonds that were traded on exchanges. In reality, equities and bonds represent only a small proportion – maybe less than one-sixth – of the total number of financial instruments that financial institutions have to process. Major data vendors now have to manage over 200 million financial instruments across all asset classes and that number is currently growing by around five million instruments a month.

Regulators are asking which instrument identifiers are used by firms, which they should use themselves and what the impact of using particular standards might be. In its current consultations on MiFID II/MiFIR, ESMA recognises that the identifier standards that have traditionally been used for equities and bonds have been adopted very little across the breadth of asset classes they have to address. Estimates are that perhaps some 30 million ISINs – International Securities Identification Numbers – have been issued around the world which falls far short of the 200+ million instruments (and growing) that need to be identified.

For derivatives, ESMA has recommended the use of Alternative Instrument Identifiers, a format originally proposed by the Federation of European Securities Exchanges when MiFID I was being implemented and the scale of this problem was first recognised. Rather than being an ‘identifier’ (i.e. a ‘dumb code’), an AII is really a descriptor – a collection of different data fields that describe the instrument in question. An AII is not a recognised industry standard and it is not used outside the EU, or other than for regulatory reporting purposes within the EU, but ESMA has also recognised that AIIs won’t provide coverage of all of the necessary instruments either.

Meanwhile, ESMA has been faced with a very similar problem when it comes to identifying hedge funds and other alternative investment funds under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive, but has taken a different approach. Rather than creating a new format or standard for an instrument identifier, ESMA has allowed fund managers to re-use identifiers they already deploy when they are marketing their funds and publishing their performance to investors around the world via data vendors.

The difference in these approaches is at the heart of perhaps one of the most relevant questions firms and regulators need to consider about instrument identifiers: should the industry be shifting towards a single global standard for identifying all financial instruments in the world or should firms today be allowed to re-use instrument identifiers they already deploy? Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic are grappling with questions about the use and characteristics of industry standards. The answers will define and transform the way they monitor financial markets and ensure their integrity for future generations.