CFPB Issues Final Prepaid Rules; Expanded Definition Worries Industry

The U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) on Oct. 5 released its final rule on prepaid accounts, a move that sharply expands the definition of prepaid—to the distinct displeasure of prepaid industry players. The new rules, which take effect Oct. 1, 2017, are quite similar to what the CFPB initially had proposed, with provisions tweaked in the final rule, rather than major additions or deletions.

The U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) on Oct. 5 released its final rule on prepaid accounts, a move that sharply expands the definition of prepaid—to the distinct displeasure of prepaid industry players. The new rules, which take effect Oct. 1, 2017, are quite similar to what the CFPB initially had proposed, with provisions tweaked in the final rule, rather than major additions or deletions.

CFPB officials said the changes will have little serious effect on what retailers and consumers have to/can do with prepaid cards, but it is changing quite a few of the behind-the-scenes requirements. Things may not change in practice, but the legal protections will change, said one CFPB official.

The bureau characterized the changes as delivering “strong federal consumer protections for prepaid account users” and said some of the new rules require “financial institutions to limit consumers’ losses when funds are stolen or cards are lost, investigate and resolve errors, and give consumers free and easy access to account information.”

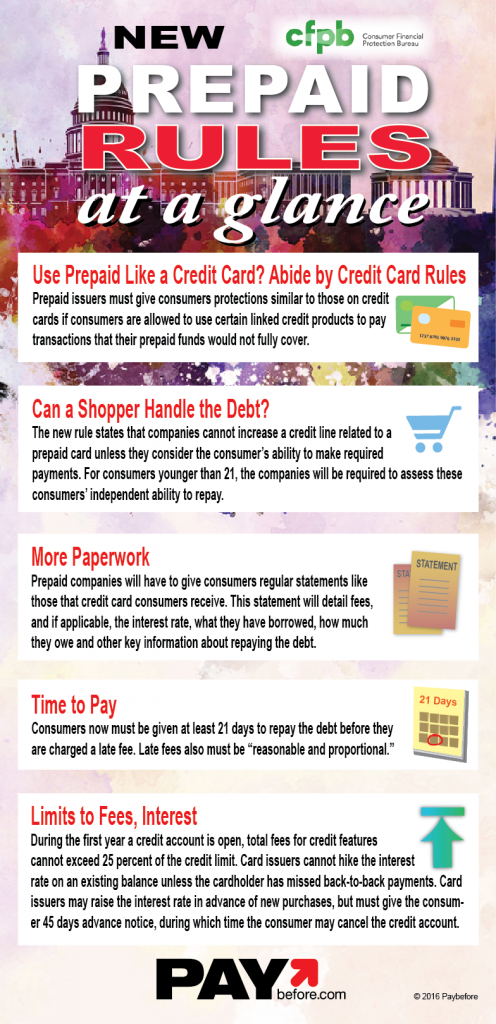

The CFPB also said new Know Before You Owe prepaid disclosures “give consumers clear, upfront information about fees and other key details” and that the new rules will force prepaid companies to “offer protections similar to those for credit cards if consumers are allowed to use credit on their accounts to pay for transactions that they lack the money to cover.”

Many of the new rules (see at-a-glance box) focused on prepaid overdraft, where the cards can tiptoe into territory normally occupied by some debit products and all credit products.

Many of the new rules (see at-a-glance box) focused on prepaid overdraft, where the cards can tiptoe into territory normally occupied by some debit products and all credit products.

Ben Jackson, who oversees prepaid coverage at The Mercator Advisory Group, was taken aback by how much the CFPB focused on prepaid overdraft. “The actual incidence of prepaid overdraft is minuscule. I only know of two companies offering it,” Jackson says. “I don’t know why (CFPB) obsessed over this.”

Some could say that bureau lawyers obsessed about quite a bit, given that they took their initial proposed rule changes—which were published at a respectable 870 pages—and turned out a final rule that was 1,689 pages long.

“That’s five times the size of Durbin,” Jackson says.

The CFPB defended the heft, saying the final rule is actually fewer than 100 pages and that the rest is commentary and appendices that accompany the regulatory text, as well as background information, a section-by-section analysis of the final rule, and regulatory impact analyses.

A key point stressed by industry observers who took an initial look at the massive document is that the definition of prepaid has sharply expanded. This worries industry leaders such as Brad Fauss, president of the Network Branded Prepaid Card Association (NBPCA), who are concerned that it might drive out some vendors afraid of the additional compliance and associated costs.

Fauss said his association “is concerned that imposing Regulation Z requirements on overdraft products could lead to their elimination from the marketplace at a time when income variability is increasing consumer demand for these types of products and customer satisfaction remains at high levels.”

The NBPCA “agrees with the bureau that prepaid products consumers use as their primary transaction accounts should have similar rights and protections as traditional checking accounts,” Fauss says. “However, the definition of prepaid account in the final rule is so broad that it encompasses many of the more than 15 different types of prepaid cards in market, some of which likely will not withstand the increased costs of compliance.”

An attorney who specializes in prepaid products, Eli Rosenberg of Baird Holm LLP, also sees the prepaid definitions as problematic. “It’s probably overly broad and it will pull in a bunch of products that it shouldn’t,” Rosenberg says. “It’s still a net negative.”

The rule applies to traditional GPR prepaid cards, mobile wallets, P2P payment products and other electronic accounts that can store funds, according to the CFPB. In addition, the rule pertains to payroll cards, student financial aid disbursement cards, tax refund cards and certain federal, state and local benefit cards, such as those used to distribute social security benefits and unemployment insurance.

“In what can only be described as bureaucracy run amok, what started out as an effort to define appropriate consumer disclosures by the CFPB, which could have been accomplished in less than 10 pages, is now a 1,600-page document that impacts not just prepaid but also P2P offerings, PayPal, and even E-ZPass tolling systems,” says Tim Sloane, Mercator’s vice president, payments innovation. “While lawyers and paper mills profit, the unbanked and underserved, which were supposed to be protected by this regulation, will now see higher prices and fewer choices as suppliers with low volumes and profits become unsustainable under the weight of this regulation and pull out of the market.”

The CFPB said E-ZPass does not, in fact, meet its definition of prepaid, as it’s closed-loop.

Sloane, however, said that CFPB’s phrasing in its new rules indeed means that it would be—or at least should be.

E-ZPass “wasn’t excluded so CFPB will need to specify that E-ZPass is excluded as they go forward. The definition given in the rules clearly would include E-ZPass,” Sloane says. He cites the following language in the rule at issue: “It covers accounts that are marketed or labeled as ‘prepaid’ that are redeemable upon presentation at multiple, unaffiliated merchants for goods or services, or that are usable at automated teller machines (ATMs). It also covers accounts that are issued on a prepaid basis or capable of being loaded with funds, whose primary function is to conduct transactions with multiple, unaffiliated merchants for goods or services, or at ATMs, or to conduct person-to-person (P2P) transfers, and that are not checking accounts, share draft accounts, or negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts.”

Sloane argues that “the CFPB rules used ‘or,’ which means meeting either definition is sufficient. So I would suggest that E-ZPass is an ‘accounts that are marketed or labeled as “prepaid” that are redeemable upon presentation at multiple, unaffiliated merchants for goods or services’ while not useable at ATMs. Note that E-ZPass was submitted as evidence of wide adoption of prepaid in a state court case involving Simon Malls and that Mercator has included E-ZPass as part of prepaid since the inception of the prepaid benchmark.”

CFPB contends that E-ZPass is not a multi-retailer supported offering, but Sloane counters that its acceptance in multiple state systems is comparable. “I would argue that E-ZPass is no longer a closed-loop system as it is structured more like SNAP with states controlling the accounts and enabling many merchants to participate using a restricted authorization network (RAN) that would appear to me to fit the CFPB’s definition until they offer it a carve out,” Sloane says.

Asked by Paybefore to explain the definitional changes, this is what CFPB said and, given the significance of the prepaid definition, we offer the bureau’s e-mailed excerpt from the new rules, in its entirety.

“Specifically, the Bureau has reorganized the structure of the definition and added certain wording to the final rule that is designed to more cleanly differentiate products that are subject to this final rule from those that are subject to general Regulation E. First, to streamline the definition and to eliminate redundancies, the bureau removed the phrase ‘card, code, or other device, not otherwise an account under paragraph (b)(1) of this section, which is established primarily for personal, family, or household purposes’ from the final rule’s definition. Second, the CFPB is clarifying the scope of the definition by adding a reference to the way the account is marketed or labeled, as well as to the account’s primary function. Under the final definition, therefore, an account is a prepaid account if it is a payroll card account or government benefit account; or it is marketed or labeled as ‘prepaid,’ provided it is redeemable upon presentation at multiple, unaffiliated merchants for goods or services or usable at ATMs; or it meets all of the following criteria: (a) it is issued on a prepaid basis in a specified amount or not issued on a prepaid basis but capable of being loaded with funds thereafter; (b) its primary function is to conduct transactions with multiple, unaffiliated merchants for goods or services, or at ATMs, or to conduct P2P transfers; and (c) it is not a checking account, share draft account, or NOW account. The final rule also contains several additional exclusions from the definition of prepaid account for: accounts loaded only with funds from a dependent care assistance program or a transit or parking reimbursement arrangement; accounts that are directly or indirectly established through a third party and loaded only with qualified disaster relief payments; and the P2P functionality of accounts established by or through the U.S. government whose primary function is to conduct closed-loop transactions on U.S. military installations or vessels, or similar government facilities. Other than these clarifications and exclusions discussed herein, the Bureau does not intend the changed language in the final rule to significantly alter the scope of the proposed definition of the term prepaid account.”

A key change the CFPB pointed to involves how much payment history companies must retain about prepaid transactions, an area of particular concern, for example, with payroll cards. Today’s requirements say that 60 days of history must be retained electronically and via a call center. The new rules increase that to 12 months electronically and 24 months via a call center. Rosenberg pointed out that the proposed rule changes would have required 18 months of transaction history electronically.

A key change the CFPB pointed to involves how much payment history companies must retain about prepaid transactions, an area of particular concern, for example, with payroll cards. Today’s requirements say that 60 days of history must be retained electronically and via a call center. The new rules increase that to 12 months electronically and 24 months via a call center. Rosenberg pointed out that the proposed rule changes would have required 18 months of transaction history electronically.

Another change involves when a prepaid card is lost or stolen. When that happens, a consumer’s liability has a $50 ceiling, but only if that consumer contacts the prepaid company within two days of the consumer discovering the loss. If value is stolen instead of the card—such as if a thief breaks into the card and fraudulently spends the money—then the consumer has no liability.

Although Director Richard Cordray noted that many prepaid companies currently offer consumer protections contained in the rule, the NBPCA has had lingering concerns about requirements in the proposed rulemaking, prompting the association to outline its misgivings in a 94-page comment letter sent earlier this year and during multiple meetings with the CFPB throughout the rule-making process. Those concerns apparently fell on deaf ears as most of the NBPCA’s issues with the proposed rule have now become the law of the land.

One of the sticking points remains pre-acquisition disclosures. The NBPCA has long said it supports clear, consumer-friendly pre-acquisition disclosures, but the CFPB has mandated two disclosures, a short form that will appear on card packaging and a long form that can be obtained by phone or on the company’s Website. The association fears the similar, but not identical, fee disclosures will only confuse consumers. And, not only must prepaid account issuers post agreements for accounts they offer to the public on their Websites, they must also submit their agreements to the bureau for posting on its Website, starting in Oct. 1, 2018. The CFPB believes this will make it easier for consumers to comparison shop.

Related stories: