The finance industry’s dirty little secret: what the Net Promoter Score isn’t telling you

Corporate marketers and insights professionals in the financial services sector are moving rapidly away from opinion surveys to behavioural data in their drive to better understand customers and prospects, and to predict future behaviour. This trend is based on the increasing availability of “big data”, particularly digital behaviour data, as well as the recognition that opinion surveys can be unreliable in predicting future behaviour. Think 2016 presidential election.

Yet there’s one big exception to this trend: the popular Net Promoter Score (NPS) which is used to measure customers’ intention to recommend a brand in the future. It’s a bit like asking people to predict their voting intentions, except for the fact that there is no firm, predictable Election Day when they will be asked for that recommendation, nor any sense of civic duty to motivate them to express their opinion.

The NPS is based on a simple question that asks customers how likely they would be to recommend a given brand in the future, on a scale from zero to ten. The people who answer with a nine or a ten are labelled as “promoters”. The score is based on subtracting the percent who answered zero to six, or the “detractors”, from the percent who are promoters.

Many financial service companies have adopted this metric to gauge the quality of customer relationships – in fact, some companies link executive bonuses to achieving improvement on the metric. The problem is that the question isn’t accurately predictive of a customer’s actual recommending behaviour.

A recent Engagement Labs study for a major investment company that uses the NPS, which measured actual recommending behaviour over the past year, yielded surprising results. About one-third of the people who are considered “promoters” hadn’t recommended that brand at all over the last 12 months. In contrast, one-third of the “non-promoters” had, in fact, recommended the brand despite not being labelled “promoters”.

Many brand customers gave themselves a nine or ten on a ten-point scale of likelihood to recommend, yet they never do it. Why? They may have interpreted the question not so much as a prediction of their future behaviour, but as a proxy for satisfaction with the brand. Or, these consumers could be suggesting that the investment company deserves to be recommended based on excellent performance. But don’t expect them to be the ones to do it. It’s not in their nature.

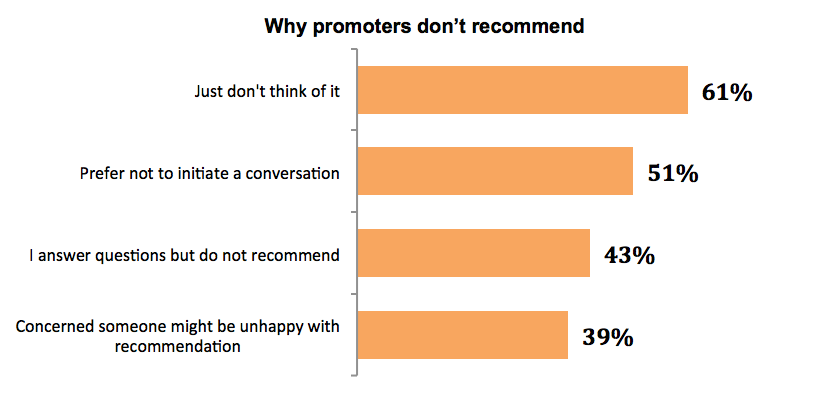

We asked people in the same survey to give reasons why they don’t give advice more often, and a majority of the “promoters” who don’t actually recommend said they don’t think of it or prefer “not to initiate” a conversation. About four in ten of them will reactively answer questions about the financial company, and explain they worry about giving bad advice.

It turns out that true brand advocates are not only satisfied with a brand’s performance, but they also have a certain personality type. They like giving advice and have plenty of opportunities to do so. They don’t worry that somebody might be unhappy with the advice and hold it against them. These brand advocates acknowledge that there are risks involved with having a strong recommendation in a category like investments, where bad advice could mean the loss of a person’s retirement savings.

Thus, the key to determining future recommendations is to measure recent, past behaviour, not a person’s willingness to recommend. The people who are recommending a brand last month will be the ones who are also most likely to recommend it again next month.

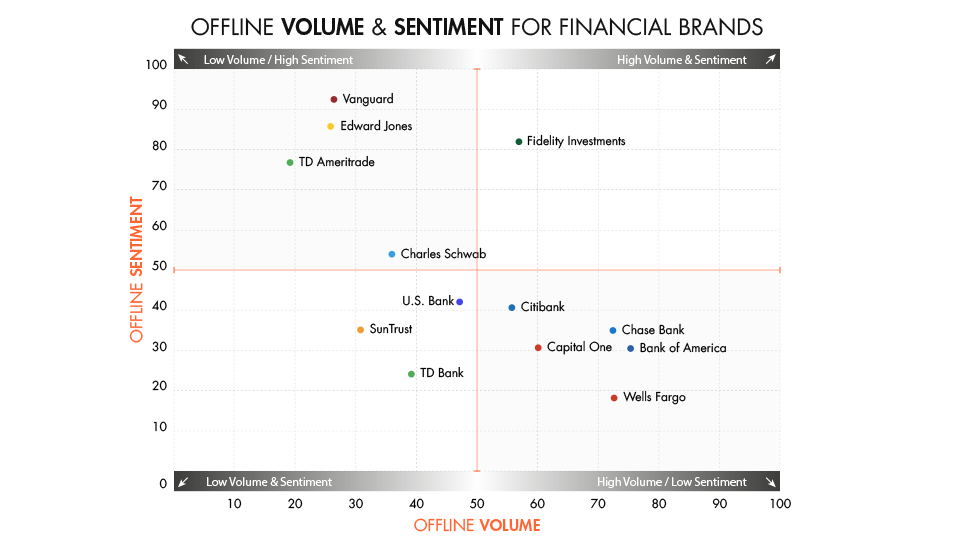

So, how are the major financial brands performing in terms of actual recommending, rather than future intentions? One way to look at the issue is to consider both the volume and sentiment of conversations – measuring the overall amount as well as how positive the conversations are. In the chart below, Vanguard and Edward Jones are leading the way among their competition with the most positive conversations and recommendations.

Meanwhile, we see the leaders in conversation volume are Bank of America, Chase, and Wells Fargo – these institutions are receiving the largest number of conversations, even if they are not particularly enthusiastic. But the brand in perhaps the best position is Fidelity, which gets a lot of conversations (high volume), and generally very positive ones (high sentiment).

Almost every financial services company in our research has a chance to improve. For example, Vanguard and Edward Jones lack in being able to get their happy customers to recommend them more frequently due to their low volume scores. On the other hand, Bank of America and Chase should be focused on improving the customer experience so that their frequent conversations are more positive. Falling behind on both sentiment and volume, however, Suntrust and TD Bank are two brands that need to work on both things.

“Would you recommend us to a friend?” It’s a simple question, and worthy of achievement by financial companies. But it’s not a strategy. And because we know that actual conversations drive about 19% of all consumer purchases – your focus should be on consumer behaviour, not good intentions.

By Brad Fay, chief commercial officer, Engagement Labs

Always pleased to see documented evidence of why recommendation is a deeply flawed CX performance metric. Have studied and reported the challenges associated with NPS, Satisfaction, and Customer Effort Score for over a decade: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-oh-anybody-still-measuring-customer-satisfaction-michael/