The perennial BNPL crown

The BNPL sector has exploded this year

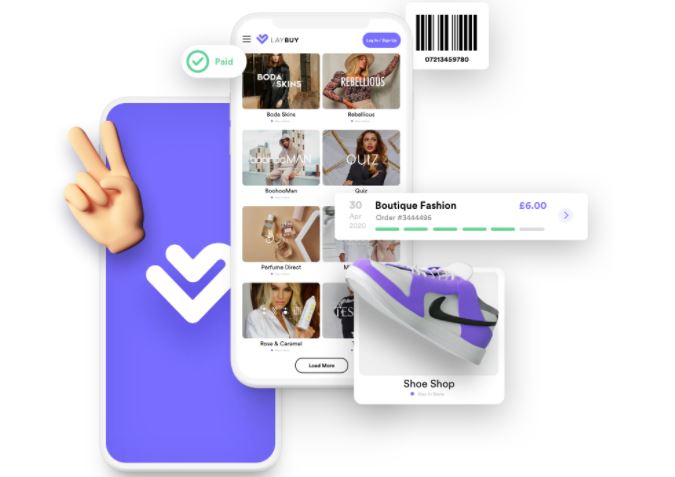

One of my very first face-to-face interviews for FinTech Futures was with Laybuy, a New Zealand-founded buy now, pay later (BNPL) fintech looking to make it big in the UK. My editor and I sat across from the founder, Gary Rohloff, in an uncomfortably loud café. When Rohloff explained how the fintech made money, he stressed the “interest free” component – unlike some of Klarna’s products – cushioned by the 4% commission imposed on merchants.

It all sounded pretty rosy to me at the time, and I remember saying to my editor: “Are we missing something here?” Upon revisiting the interview, I did a little digging on Trustpilot to see what customers had been saying since its UK launch began. A common complaint is that the firm, which takes six instalments in total, will continue to withdraw payments even if the item is faulty or refunded. Other customers claim to have only received partial refunds – some as low as 25% of the original purchase. When I interviewed Rohloff back in August 2019, he said Laybuy’s return figures sat as low as 5% of order totals. When I think of how many times I’ve returned things to ASOS, I find this hard to believe.

Klarna’s business model, which includes interest-weighted products as well as interest-free options like Laybuy, has become the subject of a “KlarNAA” campaign. It’s seen Generation Z’ers and young millennials call out the fintech for drawing users into debt-fuelled spending without making the risks clear. This has led to the Woolard Review, set up in September to investigate unregulated credit providers like Klarna. The results, set to land sometime in 2021, won’t affect the likes of Laybuy, whose interest-free model doesn’t come under the consumer credit umbrella.

And even if some consumers feel misguided or know the risks these platforms entail; many people are still using them blindly. A Compare the Market survey this year found that more than 40% of BNPL users were unaware missed payments could affect their credit scores.

Such blind allegiance has seen the BNPL sector explode in 2020 when it comes to market value. Australia is further ahead than the UK because it’s housed the products for longer. In August, the Financial Review highlighted the rise of Melbourne-born BNPL king Afterpay. Its value has risen 922% to a $18.7 billion market capitalisation in just eight months. “This is a stock that looked expensive in February at just shy of AUD 40 ($29.4). At AUD 91 it looks irrational.”

So, what is the logic behind such enormous, “irrational” valuations? In short, the business model does make sense – even if its literal goal is to encourage young consumer debt. Afterpay, which broke into the UK under sister brand Clearpay – saw its losses halve between 2019 and 2020. Credit losses are also falling as customers become more enamoured with the service.

Unlike payday lenders, which are largely extinct in the UK after being hit with a wave of compensation claims for mis-sold loans, BNPL firms put the majority of risk onto the consumer – who is hit with the late fees, interest and bad credit scores. Klarna’s annual percentage rate (APR) in the UK is 18.9%, still a good few percentage points lower than the typical credit card, highlighting just how little risk these firms are taking on.

The problem with this model is that it’s very one-way. Which the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) could change next year – though as we said, it will only affect BNPL firms which charge interest.

It’s a sad picture to envisage. As the country descends into part two of what feels like a never-ending economic downturn, young consumers – many of whom already struggle with student debt – are the ones at the heart of retailers’ “let’s-get-back-on-track” revenue strategies, with BNPL fintechs as the profiteering enablers.