Has JP Morgan Chase learnt the lessons of Finn and Bó?

JP Morgan Chase has finally broken its silence over plans to launch a consumer digital bank in the UK. Since unofficial reports first landed in August last year, the major US bank hasn’t – until now – clarified its position on the expansion.

But in an announcement on Wednesday, JP Morgan Chase said it had already hired 400 people to operate its first ever UK arm. The new operation is set to land “within months”.

Its US rival, Goldman Sachs, has already enjoyed notable success with its UK consumer brand Marcus. The bank launched more than two years ago.

For JP Morgan Chase, this isn’t its first challenger start-up foray

Sanoke Viswanathan, JP Morgan’s chief administrative officer for its corporate and investment bank, will head up the new, Canary Wharf-headquartered digital bank. It will also house employees in a new call centre based out of Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital.

“The UK has a vibrant and highly competitive consumer banking marketplace,” says Gordon Smith, the bank’s CEO for consumer and community banking. “Which is why we’ve designed the bank from scratch to specifically meet the needs of customers here.”

In November, The Times reported that JP Morgan was eyeing up UK challenger Starling Bank’s two million customer base. But with Starling’s CEO, Anne Boden, refusing to sell up to a big bank, it seems JP Morgan will have to either consider a smaller acquisition or grow its customer base from scratch like its US rival.

JPMorgan Chase’s failed US attempt

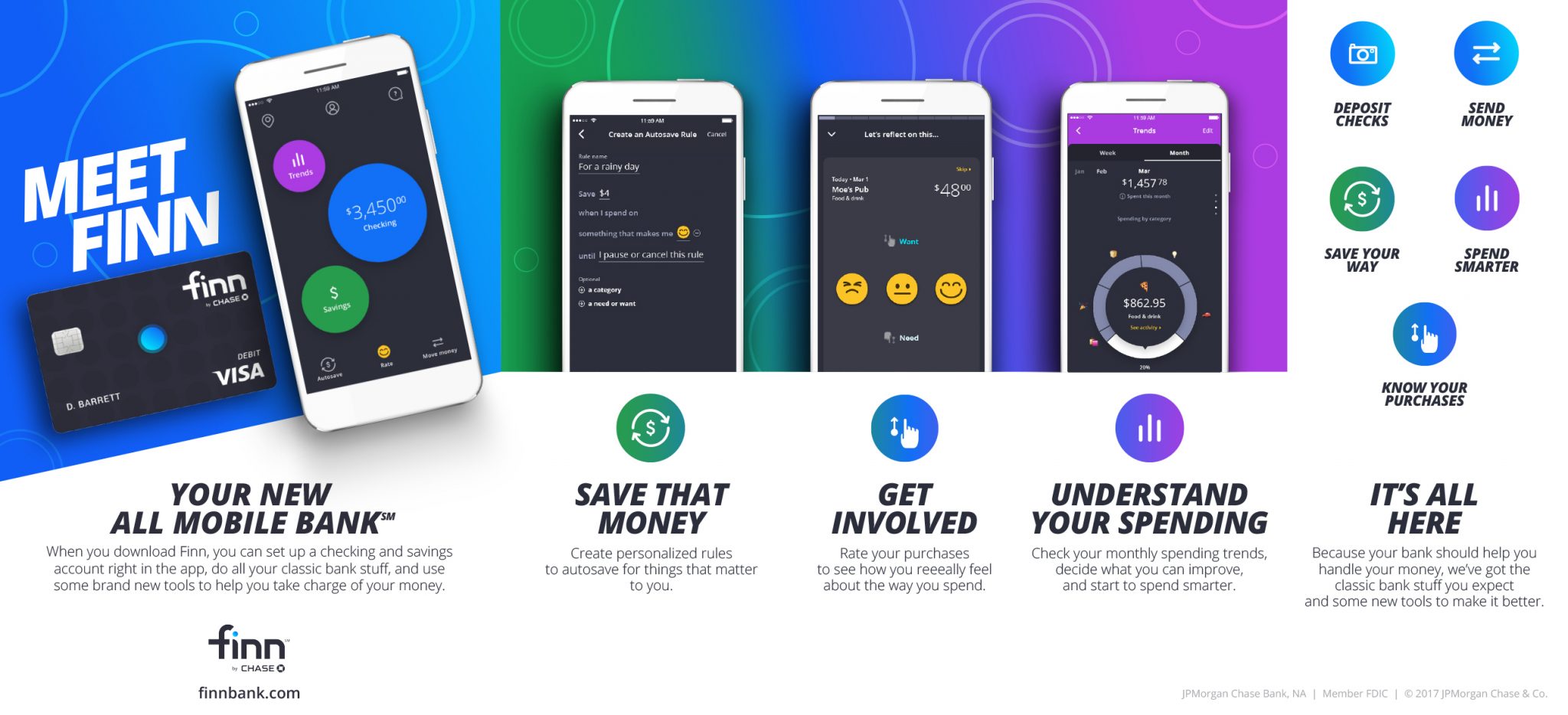

For JP Morgan Chase, this isn’t its first challenger start-up foray. In 2017, it rolled out digital bank, Finn, over in the US. But a year later, it shuttered the challenger.

The bank never revealed customer numbers for Finn, but at the time Forbes cited Cornerstone Advisors estimates. They suggested the digital challenger only onboarded 47,000 customers.

JP Morgan’s Finn launch in 2017

A Business Insider report highlighted some of the reasons why Finn failed. One was down to that fact there wasn’t a significant difference between Finn and JP Morgan Chase’s own mobile banking app. Largely because they sat on the same backend structure.

And just as it unveiled Finn, the bank also announced the roll out of 400 new bank branches over the next five years. Such a move removed the need for a digital bank account in hard-to-tap areas.

As for competition, its rival Goldman launched its savings account with one of the most competitive interest rates in the US market at 2.25%. It had already attracted billions in deposits.

Bó – the UK’s Finn

NatWest’s digital challenger bank, Bó, followed in the footsteps of Finn in the UK. The yellow card disappeared just six months after launch. It likely serves as an example to JP Morgan Chase of “how not to”, alongside its own failed attempt.

It accumulated just 11,000 customers, even less than Finn – most of which were “friends and family”. CEO, Alison Rose, called it an experiment upon closure, but it was clear the bank had intended great things for the investment.

Then chief executive, Mark Bailie, told the Financial Times in April 2019 that NatWest was aiming for “a few million” customers within five years of launch. He also said the bank was taking the project “very seriously”.

Does the UK’s crowded nature require more specific customer targeting?

The challenger struggled to ever gain momentum. In February 2020, it had to re-issue 6,000 cards to customers due to security oversight. It meant the challenger had to reveal the number of customers it had, which was lower than many had expected.

One expert told CNBC in May that the bank failed to take off due to the “crowded nature and maturity” of the UK’s digital banking market.

The UK challenger scene has moved on from the mass market play

With the constant stream of start-ups launching new challenger banks in the UK, this crowding and maturity isn’t letting up. As a result, challengers are now trying to tap very specific markets – perhaps something JP Morgan Chase should also consider.

Monument, which already has its UK banking licence, is looking to tap Britain’s mass affluent population this year. Although this bracket makes up just 5.25% of Britain, the start-up believes its holds £3.5 trillion in wealth.

Atmen, is addressing the fact no Black British-led high street or digital banks exist in the UK, despite ethnic minorities making up around 10% of the population – some 6.6 million citizens. Licensed through its banking-as-a-service (BaaS) provider, Atmen plans to serve those who have fallen victim to racial discrimination at the hands of incumbent banks. According to Warwick University research, UK banks charge Black customers higher interest rates on loans.

Perenna, set to launch later this year once its banking licence arrives, wants to offer 30-year fixed-rate mortgages. The product isn’t currently available in the UK, where terms tend to only stretch two, three or five years only. According to Bank of England data published in July, mortgages with five-year fixed rates or more account for half of all new mortgage lending in the UK – attesting to the opportunity.

Other players include Oxbury, a licensed challenger bank for British farmers. As well as Rewire, the Israeli fintech with an Electronic Money Institution (EMI) licence which is trying to connect the UK’s 9.5 million migrants with their banks back home to improve the banking offerings open to them.

Islamic finance has also enjoyed a wealth of new entrants in the last year, including Niyah, Rizq, Kestrl, and Waqfinity. In the UK, Islam is the second largest religion. Muslims make up 5% of England’s population – more than 2.5 million, according to census data.

“For a fintech, the key to success is reaching a critical mass,” Irfan Khan, founder of Islamic property-crowdfunding platform Yielders, told Sifted last year. “One way to do that is to focus on a specific segment, to penetrate that far easier and faster.”

Success of rival Marcus

JP Morgan Chase is entering yet another market where its rival, Goldman, has a substantial head start.

Goldman’s Marcus attracted too many deposits during the pandemic last year. In June, deposits climbed so high Goldman had to close Marcus’ easy access savings account to new UK customers.

Regulated deposit limits during the country’s first coronavirus lockdown climbed to £21 billion. UK banking rules stipulate that retail deposits totalling more than £25 billion must be ring-fenced – i.e. the bank would have to separate these assets from the rest.

Marcus UK’s head, Des McDaid, told Reuters last year that separating Marcus financially and operationally from the US would be “a significant change” to its “low-cost business model”.

Goldman is mulling acquisitions to bulk up Marcus

He added that this low-cost model allows Marcus “to pay consistently competitive rates to existing savers”.

Despite it attracting billions in deposits, the bank has since lowered its interest rate a number of times. This has likely caused a handful of customers to move their savings away.

Its easy access savings account went from 1.3% to 1.2% to 1.05% to 0.7% over 2020, making it far less competitive. Currently, Virgin Money offers a 2.02% easy access current account, and Chip offers a non-compounded 1.25% easy access account.

So, Marcus is no longer one of the UK’s most competitive players.

Goldman is mulling acquisitions to bulk up its UK-based digital savings and lending service Marcus, according to three Reuters sources. One area of interest is digital banking businesses, meaning JP Morgan isn’t the only bank eyeing up UK challenger deals.

With interest rates sitting at rock bottom with no sign of increasing, it offers JP Morgan Chase a slightly more even playing field than it had upon Finn’s launch. But that means the digital bank will have to discover an alternative pull for customers, as Marcus’ success has largely been based on its – until now – impressive interests rates.

Read next: JP Morgan and Lloyds considering acquisition of UK challenger Starling Bank