Kalifa report says UK’s fintech crown at risk from waiting competitors

Ron Kalifa’s wide-ranging report into the UK fintech industry released this week, warning other countries are waiting in the wings to snatch its “crown”.

The UK’s fintech sector, generating £11 billion ($15.6 billion) a year for the country’s economy, now holds a 10% share in the global fintech market.

But whilst Kalifa’s report celebrates UK fintech, it also highlights the fact the sector has hit an inflection point of opportunity and risk. To mitigate the risks posed to UK fintechs, particularly post-Brexit, the report lists a number of recommendations. “[They] must be done now,” says Kalifa. “Others are waiting for our crown to slip.”

The UK’s fintech sector continues its growth

A reliance on foreign talent

One relates to attracting international talent. As revealed earlier this week, Kalifa has proposed a “tech visa” with the backing of UK prime minister Boris Johnson, and lobby group Tech Nation.

These would give priority access to workers in the tech industry to live and work in the UK. According to Kalifa’s report, foreign talent represents around 42% of UK fintech employees.

Homegrown fintechs such as Transferwise, Monzo, Checkout.com, Revolut, and Onfido collectively hold a valuation north of £19 billion ($27 billion). Their contributions to the UK economy are huge, but they rely on an easy flow of workers onto the island.

“The proposed introduction of a new visa stream will no doubt serve to attract qualified talent and boost the international appeal of the sector,” says Ammar Akhtar, Yobota’s CEO.

Another way the report wants to boost the UK’s fintech status internationally is to create a “Fintech Credential Portfolio” (FCP). It says this would “mitigate barriers to entry” and “in turn further ease collaboration between fintechs and larger firms in the market”.

Oliver Prill, Tide’s CEO, thinks the FCPs have “the scope to ease market entry significantly”.

Getting local

Adam Holden, NorthRow’s CEO, thinks “regional funding”, as opposed to just London-focused investments, will help to attract the right talent to the UK’s fintech sector.

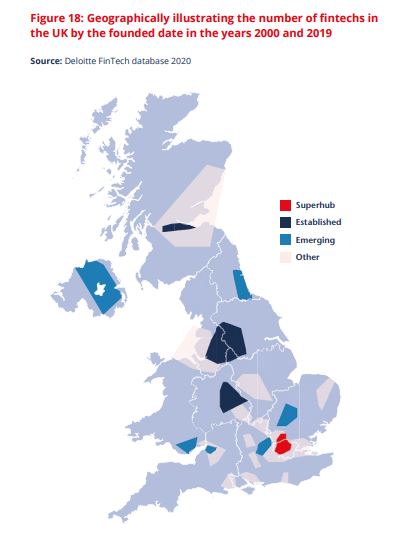

One of the report’s recommendations highlights the need for better “national connectivity”. It suggests establishing ten fintech clusters across the UK, each tasked with writing their three-year strategy for growth.

They would be located in London, the Pennines (which would cover Manchester and Leeds), Scotland, Birmingham, Bristol & Bath, Newcastle & Durham, Cambridge, Reading & West of London, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Each cluster would be categorised as either a “super hub”, “established”, “emerging”, or “other”.

In Manchester, the fintech scene has historically put less emphasis on connectivity alone. Instead, putting more weight on the end goal of growing its own fintech unicorn.

Scaling to IPO stage

Kalifa highlights the much-criticised issue of scaling fintechs in the UK. The report wants to boost the lagging number of London initial public offerings (IPOs), especially compared to countries like the US.

There were just 30 IPOs in London last year. Two thirds of these took place in the last quarter of 2020.

One proposal is to implement a “scalebox” which would support fintech scaleups as opposed to the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) regulatory sandbox, which incubates start-ups.

The scalebox would allow established firms to test new products designed to grow their customer bases. Just like the regulatory sandbox, it would offer firms an easier pathway into large customer contracts – be them with banks, or other enterprise-level customers.

Alongside the proposed scalebox, Kalifa says government should get more involved and form a “Digital Economy Taskforce” (DET) which could write a policy roadmap for fintech development.

Former Worldpay chairman Kalifa also recommends a £1 billion Fintech Growth Fund, in an effort to tackle what it calls “a £2 billion fintech growth capital funding gap”.

But as Charles Delingpole, ComplyAdvantage’s CEO, points out: “The government needs to be mindful that there is already a huge number of commercial growth and venture capital funds in the UK.”

These suggestions, the report hopes, will make the UK a better location to grow fintechs into listed companies. This year is already looking better, according to technology sector specialist at the London Stock Exchange (LSE), Neil Shah.

“The 2021 pipeline for tech IPOs in London is very strong. With more tech floats expected in the first half than in the whole of 2020,” Shah told CNBC at the beginning of February.

Dual class changes, no Spacs

In this vein, the report also calls for a “free float reduction, dual class shares and relaxation of pre-emption rights”. All these regulatory changes would likely attract more companies to go public in the UK, as opposed to the US.

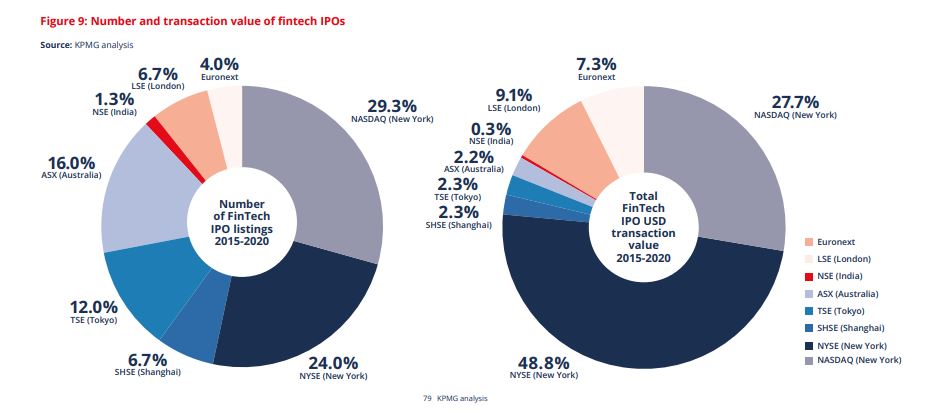

As Kalifa’s review points out, out of the 3,787 IPOs at the world’s major stock exchanges between 2015 and 2020, the US

alone accounted for 39% (via the NASDAQ and the NYSE), while the UK trailed with 4.5%.

But some are sceptical of dual class structures, and think there are more important changes needed to the LSE. “In reality the practice [of dual shares] is few and far between,” says Delingpole.

“Probably far more relevant is the take-over code rules on change of control, which makes special-purpose acquisition companies (Spacs) difficult to list in the UK.”

Last year saw a huge flurry of Spac-fuelled IPOs. In the US alone, 244 took place, raising more than $78 billion between them – according to Refinitiv data.

Whist Kalifa’s report doesn’t mention Spacs, it does call out the Competition and Market Authority (CMA), suggesting the regulator is at present a hindrance for fintech.

“There is a case for more flexibility in the assessment of mergers and investments for nascent and fast-growing markets such as fintech,” it reads.

As of December last year, the CMA had prohibited more mergers via a “phase 2” than it had cleared, with a further six transactions abandoned by parties, according to Ashurst data. Phase 2 sees the regulator launch an in-depth assessment into a merger.

More difficult post-Brexit

Ian Connatty, managing director at British Patient Capital, puts this slow London IPO timeline down to a lack of “both access to talent and easy access to global markets”.

UK fintech Currencycloud’s CEO and self-proclaimed Silicon Valley veteran, Mike Laven, says from his experience “fintechs need assurance of these things from the start”. He adds: “Unfortunately, the fallout of Brexit and the pandemic have recently made this more difficult.”

“It’s shocking the elephant in the room with Brexit is never acknowledged”

One of the ways Railsbank’s Verdon thinks the UK can overcome this is by drawing parallels with Scandinavia. “Where companies know how to grow globally because the local market is so small”. This, in addition to a fintech-friendly tax environment, is why Verdon sees “cause for optimism”.

The UK is striving to cultivate an equivalent financial environment with the rest of Europe. This is an approach it hopes will maintain the country’s financial stability in the long-term, beyond 2022 grace periods.

But the Bank of England’s governor, Andrew Bailey, said on Wednesday that the EU’s initial efforts to help the UK achieve equivalence to the rest of Europe have become a “sideshow”.

The governor accused the European Commission of being more concerned with pulling billion-euro derivatives clearing business out of London.

These actions, confirmed in EU documents seen by Reuters, directly contradict the sort of “equivalence” supposedly set to underpin the UK’s post-Brexit memorandum of understanding with Brussels.

Nigel Verdon, Railsbank’s CEO and a Kalifa report participant, points out that “equivalence” aside, the UK fintech sector has already spent “millions to set up mirrored infrastructure in Europe”. The Kalifa report recognises this too.

“It’s shocking the elephant in the room with Brexit is never acknowledged,” says Verdon. “The market dropped from 720 million people to 60 million overnight”.

Read next: Manchester’s fintech scene needs a homegrown unicorn, says report