Regtech: watching personal mobile devices in financial services, but why?

Market abuse is a hot topic that the banks prioritise on a daily basis implementing heavy surveillance measures with complex technologies.

However, with the advancement of the technology the new hot topic or one of those “elephant in the room” conversations banks like to avoid is the effectiveness of soft policies for monitoring personal mobile devices on trading floors. To avoid market abuse via personal mobiles and ultimately to help protect the consumer, banks and financial services organisations have to, and now can do, more.

The monitoring of personal mobile devices is carried out through “soft policies” which are based on trust rather than compliance. These are simply ineffective, especially now with traders returning to offices and revised layouts to account for social distancing. This provides a greater challenge for supervisors/spotters to identify breaches. With home working continuing for the foreseeable future, regulators and financial service organisations are not moving fast enough to mitigate this enhanced risk and ultimately protect the consumers.

The penalties for non-compliance aren’t just financial. A 2013 Insider Trading Policy of TherapeuticsMD Inc. reveals that, in the US, it can lead to a prison sentence of up to 20 years, a maximum criminal fine of up to $5 million and, for “non-natural persons” (such as an entity whose securities are publicly traded), the fine is up to $25 million.

This raises the following question: if fines are so severe, then why does material non-public information (MNPI) abuse continue? This is because:

- It is easy.

- The introduction of personal mobile devices into regulated spaces opens this up – including the potential for market abuse to occur.

- Regulations are not widely enforced.

Amongst other remedies are civil sanctions, including: “injunction[s] and may be forced to disgorge any profits gained or losses avoided. The civil penalty for a violator may be an amount up to three times the profit gained, or loss avoided as a result of the insider trading violation.” The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) even offers bounties to persons who provide information that leads to “the imposition of a civil penalty”.

More recently, Morgan Stanley’s two most senior commodities traders lost their jobs due to using WhatsApp and other unauthorised messaging platforms, in breach of the company’s policy that restricts the banks’ communications to channels that it can monitor.

Deloitte’s Financial Services Insights, “The future of work: new challenges for trade surveillance and good customer outcomes” published in January this year, discusses compliance challenges faced by banks and financial services organisations. The report says: “increased difficulty in monitoring the use of personal or unmonitored devices creates an additional risk of insider information being inappropriately disclosed, either internally or externally to a firm”.

Raili Maripuu, CEO of Mobilewatch, explains: “From the outset, personal mobile devices are one of the biggest security threats to any business and its [corporate] material non public information (MNPI). Over the past ten years, mobile device security issues have evolved from straightforward interception to complex threats, such as unsecured apps, spyware, network spoofing and phishing. The smarter the phone, the more vulnerable and hackable it is.

“On leading trading floors, in 95% of the cases, personal mobile devices are unsupervised and unmonitored. Banks ‘comply’ on paper, but most of them have no real visibility, technically speaking, and therefore no idea what’s going on in their regulated areas. This means that MNPI can be shared without any detection, directly contributing to market abuse, not to mention breaching regulatory compliance.”

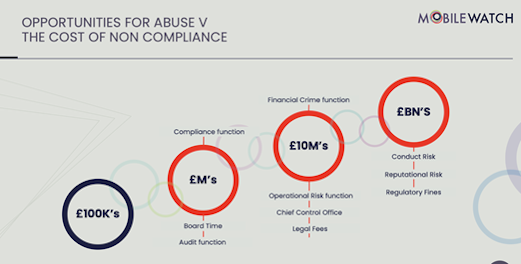

Non-compliance is costly

Is failure to achieve and maintain regulatory compliance a costly business? In December 2020, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), illustrates why it’s important to prevent market abuse of any kind. It published the following announcement: ESMA sees significant increase in EU market abuse sanctions to €88 million in 2019.

The release reveals that the National Competent Authorities (NCAs) “reported 279 administrative sanctions and measures and 60 criminal sanctions for Market Abuse Regulation (MAR) infringements in 2019. In total, approximately €82 million in financial penalties were levied for administrative sanctions, while €6 million was imposed in relation to criminal infringements of MAR.

“Despite a decrease in the number of administrative sanctions under MAR, falling from 472 in 2018, the overall financial penalties imposed are significantly higher, rising to €88 million from €10 million in 2018. This is while criminal sanctions have increased four-fold to 60, from 15 in 2018, with financial penalties rising to €6 million from €65,650 in 2018.”

However, it’s already been established that soft policies do not work. These breaches are only the tip of the iceberg. What is the true scale of market abuse? Without effective monitoring and enforcement by the regulators, it’s easy for banks to turn a blind eye. An alternative to just imposing fines after an event, there is a clear argument to address the monitoring issue head on and impose fines for non-compliance. Banks would therefore be forced to change, ultimately resulting in greater protection for the consumer. There are several incidents that show why compliance is crucial.

Working from home

With traders and other regulated staff working from home, mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ability to monitor activity has become more challenging. Maripuu, nevertheless, says the surveillance and monitoring methodology and processes in home and office environments are remarkably similar.

Privacy concerns are the biggest issue, she finds, adding, “this too is more of a lack-of-awareness point for the banks, as the technology that monitors mobile devices is non-intrusive (passive) and only collects information that is publicly available”.

The Financial Conduct Authority’s Handbook Statistics in SYSC 10A:1.7 states: “A firm must take all reasonable steps to prevent an employee or contractor from making, sending or receiving relevant telephone conversations and electronic communications on privately-owned equipment which the firm is unable to record or copy.”

Maripuu cites Julia Hoggett, the then director of market oversight at the FCA, who said in a recent speech that the expectation going forward is the office and working from home arrangements should be equivalent. Maripuu adds: “This requirement by the regulators is no longer held back by technology. Banks are hiding behind the fact that regulators are implicit in stating what is required although not the ‘how’. The surveillance achieved in the home environment can equal that of the office, effectively extending the regulated space seamlessly for those working from home.”

Biggest risk: personal mobile devices

Despite being under heavy surveillance, most financial organisations are reliant on soft policy enforcement. She, therefore, asks: “Why bother having any surveillance and cover almost all risks with complex technologies, but leave one of the biggest security vulnerabilities, mobile devices, uncovered?”

Her response: “An analogy for monitoring personal mobile device communications with manual soft policies is that you wouldn’t manually reconcile all the trades automatically carried out each day. This is an impossible task. Technology must be utilised to monitor technology [personal mobile devices]. Firms talk about trust, when really this issue is about compliance.”

With the cost of market abuse being significant, it runs into billions of dollars to the consumers whenever market manipulation is considered. Since regulatory fines don’t equate to the expected level of abuse, some firms have historically been quite blasé about regulatory compliance. Mobilewatch finds that some firms have relied upon this imbalance, boasting that they will only move to implement technology to monitor and enforce compliance once they’ve been fined by the regulators. Yet, it can take only one bad apple to create a negative perception of the market.

Moreover, the technology can be used for corporate security, executive protection, and smart working. In fact, surveillance and monitoring are essential in any regulated space – from contractors, such as cleaners to maintenance and IT staff outside of operating hours. She explains that this is because they are all likely to carry mobile devices, and so there is a danger that they may use them in regulated spaces, even when soft clear desk policies are in place, to gain access to sensitive information. Maripuu explains “without monitoring regulated spaces 24×7 they will only capture part of the picture. Behavioural analysis, real-time and historic patterns, help identify potential areas of risk requiring further intervention in order to prevent an event. It’s better to educate and mitigate than catch and fine.”

Effective surveillance

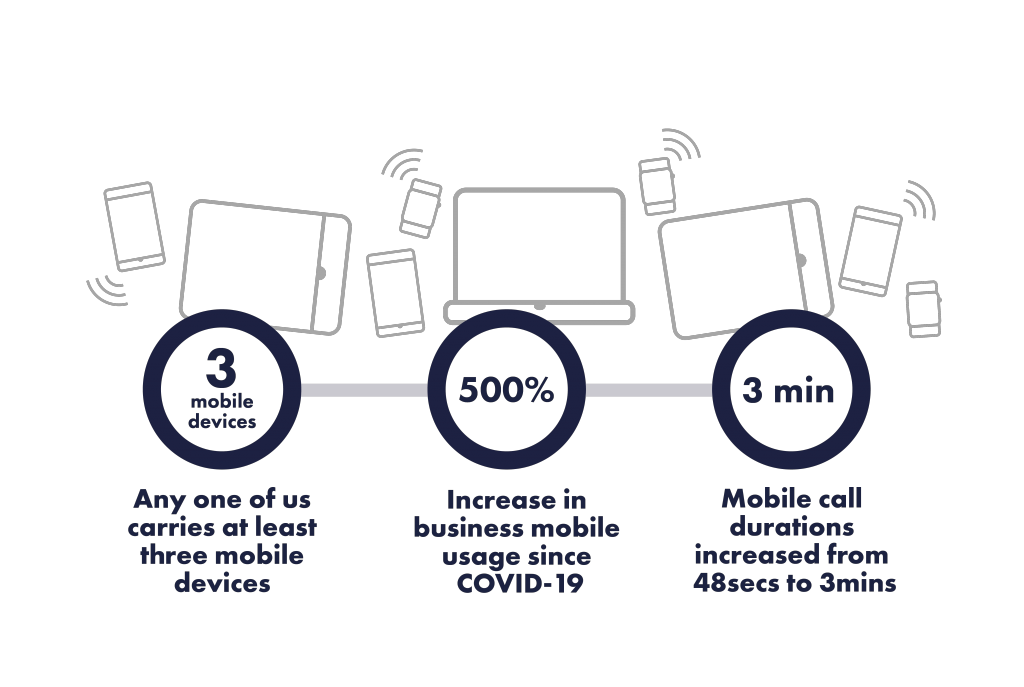

Her advice is to use the best and most effective surveillance mechanism to address any technical risks on trading floors – including for the monitoring of personal mobile devices. This also relates to corporate security in general. Realising this depends on recognising the risks present, starting with the proliferation of personal mobile devices per person. It’s then crucial to establish a realistic enforcement policy and to use technology, such as Mobilewatch’s, to address any relevant technical risk from, for example, mobile devices.

Maripuu concludes: “The best policy is one which works. Soft policies, by their very nature, do not work as intended. If they did, breaches in regulated spaces would not occur, yet regular market news demonstrate they do. Policies for the use of personal mobile devices can be whatever the firms decide.” This is why compliance can only be monitored effectively by technology, particularly as people’s personal mobiles are even more vulnerable, as most people simply don’t implement higher security settings on their phones, and so it’s vital for banks to even monitor their personal devices.

By Graham Jarvis, freelance business and technology journalist