Wintersmith

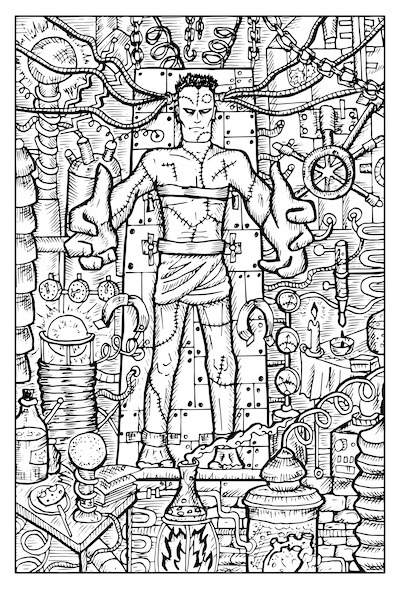

Everyone knows what you mean when you say something is “a bit of a Frankenstein”.

The word alone conjures images of an inert body on a slab, an unhinged doctor, a stormy thunderous night.

So many programmes, businesses and software projects aim to be Disney princesses but end up as “a bit of a Frankenstein”

What emerges is the stuff of nightmares and comedy alike.

An unlikely friend or a fiend?

A creature that comes about by crazed design and accident. Not pretty to look at.

It will just about stand on its feet and hobble along but it’s stitched together by pieces meant for greatness elsewhere, crudely functional but in no way attractive, elegant or, hand on heart, what we set out to do.

And that’s pretty much what we mean when we describe banking systems, projects, or business lines as a bit of a Frankenstein.

A lot of programmes, a lot of businesses, a lot of software projects start off aiming for the Disney princess status and end up with those dodgy scars across a strangely flattened head. Somewhere along the way, compromise became inevitable. Budgets became strained or politics swing away from the project’s needs so pieces of old kit have to be reused, legacy code can’t be grandfathered or, prosaically, time runs out and some bits simply have to be forced to work despite originally ambitious plans of transformation.

We’ve been there a lot over the years.

Recycling bits. Reusing old parts. Building new dreams with the debris of old.

The outcome was rarely pretty but it mostly worked. And frankly for most of my career nobody expected either elegant code or pretty UX in banking.

So Frankenstein was fine. Whatever.

And then Monzo happened. And then digital happened, whatever that was.

And nobody understood it at first but eventually early realisation dawned upon bankers and things started changing because good user experience (UX) is pretty, sure, but it’s also better and there is immense value to it.

So “digital” became interchangeable with apps, UX, “stuff happening on your screen” and that had to be pretty or at least not have giant rusty nails keeping it together so the Frankenstein approach wouldn’t do for “digital”.

The problem with that of course as we now know was that the industry’s early understanding of what “digital” entailed didn’t go deep enough. So pretty UX didn’t banish the Frankenstein approach. It just moved it along, a bit deeper inside the org but, fear not, still alive and well.

Digital capabilities teetering precariously on top of systems built for batch-based processing, static data and pre-API security provisions.

Yet slowly, painfully, the realisation that this wouldn’t be enough, dawned.

The Frankenstein of yesteryear isn’t just unattractive when compared to its digitally native brethren. It’s dead on the good doctor’s slab.

We got it. Us bankers I mean. We finally got it.

So we assembled the great and the good around our organisations and tasked them with thinking about how to fix it. Only we forgot to ensure we aligned on what “it” was.

Wintersmith

Are you a Terry Pratchett fan?

If not, don’t start with this book. It’s not his best, in my view. But it has this amazing concept of the spirit of winter deciding to take the form of a man to cause some mischief and befriend some humans.

Friend or fiend, yet again in the balance.

Only he has never been human before. He has seen a human but he hasn’t been one and he only understands what he is trying to become from the outside in.

So he creates a shape for himself that isn’t quite right even though you can’t put your finger on what is out of place, what isn’t there. It’s like… a human was created by someone who had read a few books about being human and then did their best. Which is exactly what banks did next: we held fast to our “not invented here” syndrome and tried to build the thing we needed without any prior experience.

And if you are thinking this is the digital version of a Frankenstein you are not totally wrong. But you are not right either.

Frankenstein was a patchwork of bits that had been too expensive to ditch, leftovers and systems too embedded to work around. Bits that worked even if they had started life in an altogether different structure.

Budget restrictions and shortcuts meant things were reused, their life extended past its sell-by date.

This is different.

We started from a baseline of knowing that what we had wouldn’t work. We knew we needed to build a different infrastructure. But we had never seen the inside of such a one. So we tried to catch glimpses of other people’s homework. Build or buy decisions came with extremely expensive decks from analogue consultants who were making it up as they went along. Same as us.

So we didn’t reuse body parts here.

We built a new thing. Using new technology. Trying to approximate what we thought was under the hood of things we liked while also trying to achieve business outcomes and sustainable economics the way we used to back when the world made sense.

We knew roughly what we were trying to achieve. And we used all new ingredients for it. No recycling. No Frankenstein monster this time.

But we built the new thing, in the old way.

By committee. Upfront design. Budget considerations and horse trading before the work started. Assumptions locked in when we knew the least about the journey ahead. Politics.

And more politics.

We didn’t build small and iterate. We didn’t test our assumptions and course-correct. Oh no. We analysed and planned. The steer-co voted. And we kicked off multi-stream, multi-year programmes of work. In so many banks. In so many departments. On every continent.

Don’t ask me how it’s all going.

You know the answer.

It’s not very steady on its feet. It’s not falling over. Not all the time anyway. It’s sort of looking like it should do, if you squint. If the light is right. If you have a checklist you need to work to.

But something is missing and although you don’t know what exactly what it is, you know it’s missing.

And here we are.

The Frankensteins of old reaching end of life but still standing, against the odds. And the great hope for the future of most banks?

Their very own home grown version of this digital folly, this wintersmith. Not wrong. Not recycled. Using all the right bits in all the right places and yet not quite right in ways we can’t identify so we can’t fix.

Now what?

We spent a lot of time and money and effort trying to get to here and a lot of political capital was expended with not much held back in case we need a rework… and now what?

Shall we start improvement projects? Shall we start smaller bits of work to uplift this thing? Is it even going in the right direction?

How do we start answering that?

And how do we fix what isn’t working without running the risk of creating a new, this time digital, Frankenstein. Twice removed from where we were meant to have ended up?

The technical term for this type of conundrum in the UK, for our international friends, is: a pickle.

So here we are between a rock and a hard place: if we stick with what we have we won’t go far, but if the only plan we can come up with is guaranteed to make things worse, that’s hardly a better option.

So what to do?

Call me crazy.

But if you don’t want to go backwards and don’t want to strike camp where you are because this is not where you were going, then forward is the only option.

And maybe this time what we re-use is the knowledge we acquired on the journey rather than legacy systems and body parts.

So, what have we learned?

We have learned that UX is about usability not just prettiness.

We learned that the technology under the UX is as important and can’t be faked. We learned it the hard way. But we now know.

We learned that getting the general idea and trying to build it yourself ‘because how hard can it be’ doesn’t work because it turns out it’s hard.

So now we know that too.

And we learned that knowing what you don’t know and what you want to achieve is a good place to start.

And we also know where we are and what we want to achieve and we have learned what we don’t know.

The hard way.

We learned two more things although we don’t always talk about those.

We have learned that we have a terrible habit as an industry of getting in our own way and stumbling over our own politics, presuppositions and past bets almost irrespective of wether they led to glory or not.

But it’s not all bad. Because out of this protracted mess, we learned something invaluable and life saving.

We learned how to learn. Which is amazing albeit embarrassing, what with how arrogant we have historically been about already knowing all that’s worth knowing. No matter. That’s in our past. We have become a teachable industry now. That’s not nothing.

We have also learned to recognise friends from fiends, finally.

We have learned another thing too. To stop trying to manufacture friends and start making some.

The era of the not-invented-here syndrome is over.

We have not all learned that even though it may well prove to be the lesson that determines who wins at this game.

We have learned that we can’t make the things we need for the journey. And that we need those things.

So here’s the next thing we need to learn: how to pick friends who understand the things we need for the journey ahead. People who know the bits we don’t know and make it their business to build the road we need to walk on. Hire them, buy their product, engage them. Learn from them or let them do the hard work and just benefit from the outcomes but for the love of all that is holy don’t try and make it up as you go along this time.

We know how that story ends on a stormy night and it’s not pretty.

#LedaWrites

Leda Glyptis is FinTech Futures’ resident thought provocateur – she leads, writes on, lives and breathes transformation and digital disruption.

She is a recovering banker, lapsed academic and long-term resident of the banking ecosystem. She is chief client officer at 10x Future Technologies.

All opinions are her own. You can’t have them – but you are welcome to debate and comment!

Follow Leda on Twitter @LedaGlyptis and LinkedIn.

Brilliantly articulated, as ever! Taking head-on an acute syndrome that remains everyone’s “worst kept secret” no leader tries to address.

In a slight shift of angle, I see Wintersmith as ‘Agile Frankenstein’, born out of a reportedly ‘successful’ Digital Transformation. The widespread deep misunderstanding of both DT and ‘agile’ has led to this wonder.

‘Digital’ remains to so many a definition for sexy mobile UI-s. And ‘agile’ is a bulletproof excuse for the many Errors in the trial-and-error approach in stitching together digital Fankensteins.

But the main question remains: how many leaders with expected ‘drone view’ (birds-eye is so last century) of the landscape actually see this ugly picture, lose their sleep over it, and commit to changing it?