State of play: BNPL

Each month, fintech analyst Philip Benton explores a new topic and assesses the “state of play”, providing an in-depth analysis and understanding of the market landscape.

This month we take an in-depth look at buy now, pay later (BNPL).

BNPL has become one of the most divisive credit products of the modern age.

To some, it’s the future of fairer, affordable and transparent credit, while others claim it’s the next ‘payday loan’ crisis in waiting. In truth, it is likely somewhere in-between, and a topic I’ve been keen to explore in-depth for a while.

Store finance reimagined

Purchasing something today and paying it off later is not a new concept. Walk into any furniture or bed retailer and you’ll struggle to move for the 0% finance signs being waved in your face, aiming to persuade you that the £2,500 price is not the reason you should walk out of the store empty handed. Instalment plans have always made sense for big-ticket purchases, but the popularity of store cards in the 1990s saw smaller transactions being paid in credit too.

Store cards fell out of favour as e-commerce came to the fore, but the appetite for credit remained as consumers turned to credit cards or alternative providers such as payday loans. In the wake of criticism, new regulations and payday scandals which saw many UK payday providers either banned from operating or forced into administration, BNPL started to gain prominence.

BNPL, in essence, is a win for all parties. It increases customer conversion for the merchant and is often far cheaper for consumers than traditional credit cards while providing more flexibility to pay off. However, it has garnered criticism surrounding users falling into debt and not reporting information to credit agencies, although Klarna is now doing so as of June 2022.

Old habits die hard

The Covid-19 pandemic boosted high-growth tech firms and saw Klarna become Europe’s most valuable fintech at over $45 billion in June 2021, while Aussie provider Afterpay was acquired by Block (then Square) for $29 billion in August 2021, which was the largest takeover in Australian history. BNPL benefited hugely from exponential growth online. Consumers found it more convenient to pay and, particularly at an uncertain time, it benefited users to spread payments in affordable chunks while not being subject to late fees or interest.

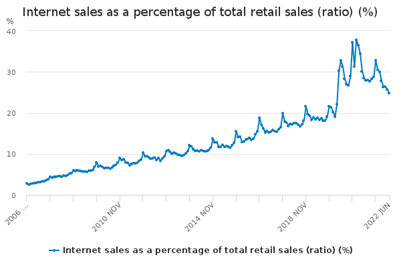

However, the expectation that this forced shift to e-commerce would become a permanent legacy of the pandemic hasn’t manifested. As the world began to resemble ‘normality’ in 2022, consumers largely returned to old habits and pandemic winners like Ocado, Zoom and Peloton started to suffer and subsequently the fintech industry as well. At the start of the pandemic, e-commerce accounted for 30% of total retail spend in the UK and peaked at 38% in January 2021, but in June 2022 it was less than 25%. This has caught the e-commerce industry by surprise and prompted mass layoffs inclusive of BNPL providers.

Innovate now, regulate later

Such is the nature of product innovation, it must gain prominence before the regulator will start to take notice. The pandemic provided the perfect storm for BNPL, with physical stores closed and bored consumers turning online to get their shopping ‘fix’ and BNPL reducing friction by enabling ‘instant gratification’ and delaying the thought of paying until the first instalment is due.

However, BNPL has only been a mainstream product for the last 5 to 10 years, so it hasn’t experienced a major economic decline, which is going to be a test as to the resiliency of the business model. You’d imagine there is going to be more demand for BNPL in a cost-of-living crisis, but it’s riskier to lend. BNPL is also subject to increasing fraud attempts, so identity checks need to evolve at speed.

Can BNPL providers afford to run the risk of late payments? Cash is king, and having a sizeable balance sheet and a cash runway is the only way to navigate uncertain times, which is why I think the likes of Klarna are willing to accept additional investment on such reduced valuation terms.

This has prompted regulators, particularly in Australia, the UK and the US, to monitor BNPL very carefully, with regulation expected to include stricter affordability checks, data protection and standardization, which will ultimately make it more challenging for BNPL providers to market their products to consumers.

Race to the bottom

Increased competition is acknowledgement that it’s a strong product. I don’t think that anyone can disagree that flexible credit with no interest or late fees is a bad thing for the consumer and it’s a very effective customer acquisition tool. However, it seems like a ‘race to the bottom’ for the traditional BNPL providers when it comes to getting your checkout button on the merchant site. Increasingly, merchants will be able to play BNPL providers off each other and negotiate cheaper rates or incite bids for an exclusive contract (this is very much Affirm’s strategy in the US having signed an exclusive contract with Amazon until 2023).

The competition for BNPL is appearing from all corners. Incumbent banks, neobanks and big tech have all launched their own take on BNPL. Apple’s play is particularly of note because they don’t need to integrate directly with merchants, plus coupled with their in-store POS terminal play, they have the ability to control the entire value chain and incentivise users and merchants alike. I wouldn’t be surprised to see the regulators keeping a close eye though due to potential anti-competition concerns.

The reasoning for banks launching a BNPL product is misconstrued. The expectation is that banks are losing out on credit card revenue due to the success of BNPL, when in fact it’s their overdraft business. Fees on ‘unauthorised overdrafts’ were banned in April 2020, which in turn boosted BNPL as consumers saw it as a more viable, affordable alternative which would avoid them dipping into their overdrafts.

BNPL 2.0: save now, pay later

From 2023, the UK government will bring into effect legislation which will ensure BNPL lenders will be required to carry out affordability checks to make sure loans are affordable for consumers, as well as amend financial promotion rules to ensure BNPL advertisements are fair, clear and not misleading. BNPL lenders will also need to be approved by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), eradicating exemptions which previously applied to interest-free products.

Step forward BNPL 2.0. This was a hot topic at the recent Money 20/20 Europe conference whereby panellists Alice Tapper (Financial Inclusion Advocate), Ruth Spratt (Zip) and Clare Gambardella (Zopa) agreed that we are at the point now where BNPL 2.0 is needed, saying that “it needs to be more structured, regulated and easier to manage”. It was also noted on the panel that “information disclosure needs to improve at point-of-sale, you can’t expect consumers to improve financial wellbeing without it”.

Zilch, a BNPL provider founded in 2018, view themselves as part of the BNPL 2.0 evolution with chief communications officer Ryan Mendy commenting that the firm is already regulated by the FCA and its strategy is different to traditional BNPL providers. He says: “We focus on having a direct relationship with the consumer instead of a finite pool of merchants, we offer 2% cashback to consumers who ‘pay in 1’ alongside 0% interest for those who ‘pay in 4’, we are seeing daily utilisation, and we conduct real-time behavioural data analysis to constantly assess affordability via a customer’s borrowing and repayment activity and revise their personalised credit limits accordingly.”

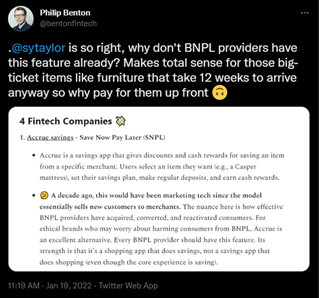

BNPL 2.0 is an easy spin for me if it pivots to ‘save now, pay later’, which is a term I first observed in Fintech Brainfood in January. As we are in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis, saving towards a specific product makes perfect sense, and particularly if you are able to obtain a discount from the merchant, as is the case with Accrue Savings’ business model. Up Bank in Australia has also launched a new savings-based feature which encourages customers to save ahead for purchases rather than pay them off. The new service means customers can now create automated savings plans for items in their online cart – dubbed a ‘Maybuy’. Once the savings goal is reached, they’ll be given the opportunity to either purchase the item or reconsider and keep the money they’ve put aside for something else.

BNPL isn’t going to suffer the same fate as payday loans simply because the fees are not so extortionate. The popularity of BNPL has prompted questions of traditional credit scoring models, which can only be a positive that will ensure credit is more available and ultimately more affordable. Banks and fintech providers have been slowly moving away from ‘financial management’ into ‘financial wellness’, and ‘save now, pay later’ is the perfect wedge product to incentivise consumers. After more of a decade of record-low interest rates and cheap debt, BNPL needs to evolve into BNPL 2.0 to ensure its relevance for the next decade.

About the author

Philip Benton is a senior fintech analyst at Omdia and writes analysis on the issues driving technological change in financial services. Prior to Omdia, he led consumer trends research in retail and payments at strategic market research firm Euromonitor.

Philip Benton is a senior fintech analyst at Omdia and writes analysis on the issues driving technological change in financial services. Prior to Omdia, he led consumer trends research in retail and payments at strategic market research firm Euromonitor.

In this column, Philip will discuss the technological implications and consumer expectations of the latest fintech trends.

You can find more of Philip’s views on fintech via LinkedIn or follow him on Twitter @bentonfintech.