Sibos 2022: Breaking new ground – banking in the metaverse

At Sibos 2022, the “Spotlight on Digital Value: Conquering the metaverse” at Swift’s Innotribe stage hashed out the arguments for banks to stake out a space in nascent virtual worlds.

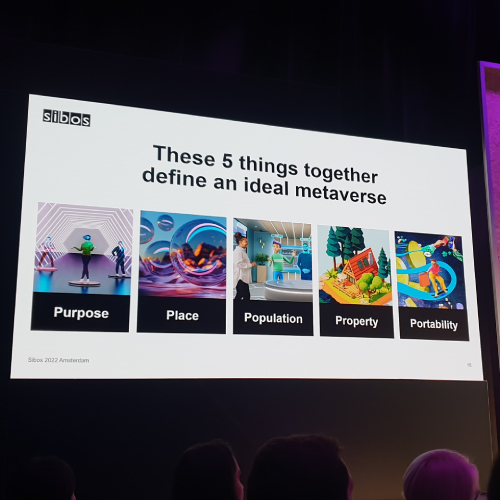

Michael Abbott, Accenture Banking’s global lead and responsible for its vision and strategy, set out to change the hearts and minds of the sceptics in the audience, making the case for setting up shop in cyberspace through a five-point alliterative argument.

His five Ps; purpose, place, population, property, and portability, gave insight into Accenture’s motivations for encouraging banks to get stuck into these unfolding virtual worlds.

“If you’re going to be in the metaverse, it starts with a purpose. You have to have a reason for being in the metaverse and banks are already starting to find a purpose,” Abbott explains.

For example, some banks are allowing people to have conversations with their financial advisors in the metaverse. “In today’s digital age where we’ve been remote for two years, that’s a unique concept, having a conversation again, maybe like we used to have in the branches 50 years ago,” Abbott muses.

At the same time, the metaverse is a place that has its own spatial logic and consistency. “Banks are already figuring this out, too. Many have joined JP Morgan and others around the world in creating their own branches in the metaverse.”

But the problem is you can create a branch, but without people you have “absolutely nothing”, Abbott says. So, the metaverse needs a population. Abbott says the best place to start in terms of populating the metaverse is internally. Bank of America is already using the metaverse, training employees on the ins-and-outs of virtual reality (VR).

Hands up

“Training for a bank robbery in the metaverse is completely different than training for it on a flat screen. It’s a whole new level of immersion.”

The metaverse is also about owning property. “If you think about Facebook today, do you own your data on Facebook? Mark Zuckerberg owns your data on Facebook,” Abbott says.

That’s the fundamental difference between the metaverse and the web. In the metaverse, you own you and your own property. Abbott takes a moment to ask the audience if they know the identity of the individual on the presentation screen, an image of a man reclining in a large, opulent virtual property.

Only one person, your correspondent, knew the answer: hip hop entrepreneur Snoop Dogg. The musician bought property in Sandbox, one of the major metaverses, for around $3 million last year.

Intriguingly, someone paid $450,000 for the house next to Snoop Dogg. Abbott then asked the bankers in the room, “how many of you are willing to lend $450,000 for somebody to buy a house next to Snoop Dogg? I see a lot of ‘no’s’ out there. By the end of this presentation, you’re going to be willing to give them that money.”

Which segued conveniently into portability. Buying and owning something is just one side of the (crypto)coin. Why own something in the metaverse if you can’t then sell it somewhere down the line? “You’ve got to be able to take that property with you and this is where it becomes critical for the banking industry,” Abbott says.

Abbott believes banks are in the best position to be custodians. “We’ve all seen the crypto news out there about how millions, billions of dollars are getting ripped off. That does not happen in the banking system because we figured out how to do the custody process. So, this is a huge opportunity for banks around the world.”

Apples and blackberries

“The key takeaway is that the metaverse is really a projection of our reality, what we do today but put into a virtual world,” Abbott explains, teeing off his five Ps. “But there’s still a reality check.”

The metaverse is still in its infancy. To demonstrate the evolution of technology, particularly technology that becomes ubiquitous and we take for granted, Abbott pulls up an Apple Newton, a proto-smartphone and personal organiser that the tech giant launched in 1993. Needless to say, it was so ahead of the curve that it flopped.

“If you were paying attention back in 1993, you could have envisioned the future.” The VR goggles and handheld controls currently needed to access virtual worlds will give way to innocuous specs and a hands-free experience. “We’re at the Apple Newton stage of the metaverse,” Abbott says.

Banks are going to take advantage of the opportunities, as they have done in the past. In 1997, Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) was the first to launch a mobile banking app on a Blackberry phone, which led to mobile banking apps that 90% of people use today. “The same thing will happen,” Abbott exhorts.

The big question is how you make money. “Banks, in my view, are motivated by two things, fear and greed, and the fear of missing out has never been higher on this one. But before we talk about how you’re going to make money, let’s step back a little bit again and remind ourselves you need a purpose.”

The purpose that will underscore the presence of banks and financial institutions in the metaverse will be making financial services more human. Accenture conducted a survey, asking tens of thousands of customers around the world, would they be interested in talking to their bank in VR. A whopping 56% said they would, “even though it doesn’t exist today”.

This is about as good of a demand as you’re going to get, Abbott says. With purpose taken care of, the next concern is payments. Every bank wants to know how they’re going to dominate but “that’s the wrong question”, Abbott says.

Reframing the question, it’s not about making payments but being able to accept payments. Again, history teaches us a lesson, this time on cooperation and collaboration.

Hands around the world

In the 1930s, store cards were introduced. Naturally, they only worked in one store, such as department store Sears. The equivalent today, Abbot says, is Roblox cash, which is essentially private label cash that you can only use inside that particular metaverse. But what happened to cards? Tired of carrying around a dozen store cards, there was consumer pressure to merge different outlets into one card.

“These closed networks started to evolve, like American Express, that allowed you to use one card at many locations.” The equivalent of that today is Bitcoin, Abbott thinks. “But eventually the banks got smart and realised if they don’t do something together, they will lose this space.”

Getting together in the 1960s, they ultimately formed the networks Visa and Mastercard. Today, Visa and Mastercard handle ten times the volume of any adjacent payment network. “The question becomes, how do you get from that second phase of closed networks to the third phase?”

Abbott says it will require collaboration, working together to create standards. “It is not going to be a winner-takes-all game,” Abbott says. In order to dismiss any naïve optimism on his part, Abbott reminds the audience that in 1973, 239 banks around the world across 15 different countries decided to get together and create the interbank cooperative Swift, which revolutionised global payments.

“They realised that there was power in collaboration and building those standards. And if we build those standards, together, it’s going to kickstart a whole new level. It’s going to allow us to put humanity back in the bank. It’s going to allow you to create mobile loyalty programmes. And on top of that, it is going to represent perhaps one of the biggest marketing opportunities out there,” Abbott says.

Concluding his pitch, Abbott signs off: “The metaverse is coming. Don’t fear missing out, build the strategy, start thinking and stay curious.”