State of play: neobanks

Each month, fintech analyst Philip Benton explores a new topic and assesses the “state of play”, providing an in-depth analysis and understanding of the market landscape.

This month, we take an in-depth look at neobanks.

With it being more than a decade since the digital-only banks movement took off, neobanks as a sector are now approaching their teenage years and quickly maturing, with talk of growth and scale being replaced by unit economics and profitability.

While incumbent banks have largely retained their customer base despite the threat of neobanks due to a combination of the limited product offering of digital-only banks and customer inertia at changing banks, neobanks are quickly expanding their product suite and adapting to a new world of alternative payments and embedded finance.

Defining a “neobank”

The literal definition of a “neobank” means “new bank”, which is derived from the Greek word νεος (neos) meaning “new”, but in practical terms it refers to a financial services provider that operates without traditional physical branch networks and exists purely online, often exclusively via a mobile app.

Neobanks saw a rise to prominence in the late 2000s in the wake of the financial crisis, during which trust was lost with the traditional banking incumbents and global regulators sought to increase competition in the banking sector by encouraging new entrants to provide banking-like services. Despite the initial push of regulators to increase competition and enable new players to provide more innovative banking services, they grew in prominence more rapidly than anticipated, which caused pushback from certain authorities about “neobanks” referring to themselves as chartered banks to avoid confusion for the customer, which forced US fintech Chime to stop using the word “bank”.

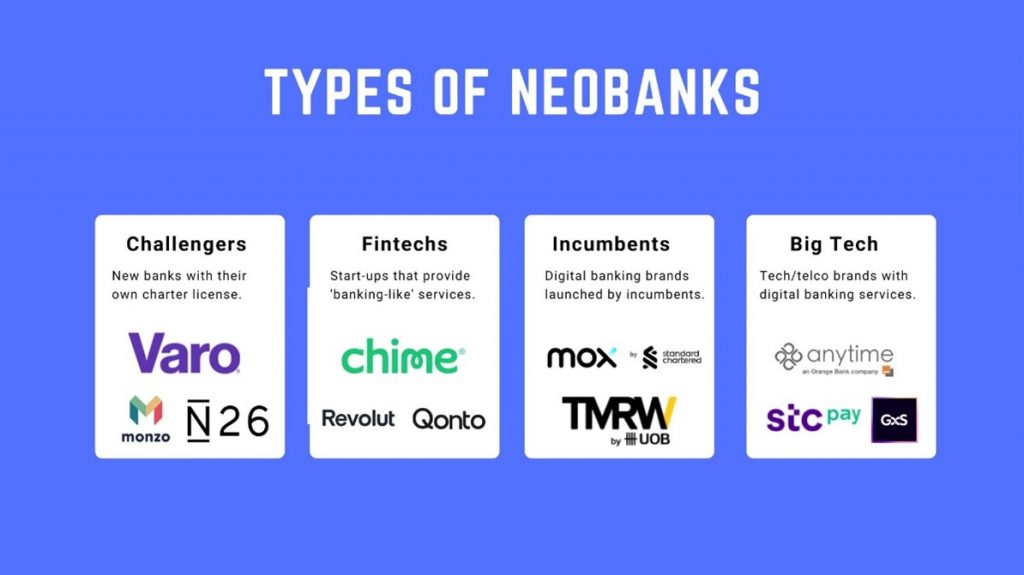

Omdia recently launched its Neobank Activity Tracker tool, which tracks over 100 neobanks of various origin across 15 categories. Our criteria to be included in the tracker is that the “neobank” is a provider of banking-like services for consumers and/or businesses and must include at least one traditional banking product – e.g. current/checking account, payment card, savings account, mortgages or loans. There are various types of neobanks, with Omdia’s definitions laid out below:

Neobanks’ nimble tech infrastructure gives them an edge over incumbents

Incumbent banks’ technology infrastructure is largely tied up in traditional business functions such as branches, ATMs and contact centres, which accounted for more than 20% of technology spending in 2022 according to Omdia’s Retail Banking Technology Forecasts. Many incumbent banks also have large workforces with hierarchical organisational structures, which makes it challenging to respond quickly to evolving market conditions.

Neobanks have been able to adopt a different approach to their incumbent counterparts. Digital banks are not laced with the technology debt of lengthy contracts or managing a large real estate, and this has enabled them to embrace modern technology stacks at a fraction of the cost. Ultimately, it means that the cost to acquire customers and maintain accounts are much lower by adopting these different approaches to building their technology infrastructure.

Many of the “challenger neobanks” that obtained chartered banking licences also opted to build their technology from the ground up. They were able to benefit from the latest technology to build and scale much more quickly, which is not only more efficient but cheaper to run. Running the architecture in a microservices cloud-native environment and utilising Kubernetes (K8s) ensures deployment can be automated, allowing product development to occur on a more frequent basis versus the annual updates that the monolithic architecture of incumbents allows.

The emergence of neobanks has also spawned the creation of an entirely new category of fintech to support these start-ups, known as Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS). Deloitte has defined BaaS as “the provision of banking products and services through third-party distributors”. In essence, this means that many of the core building blocks of a bank, from processing to card issuing, are provided in a neat off-the-shelf technology stack.

This enables neobanks to reduce both their speed-to-market and potentially the cost on the nuts and bolts of their business and focus instead on their product offering and how to differentiate their digital banking brand in a highly competitive market. This particular approach makes sense for non-financial services providers entering the space because they are unlikely to have the in-house expertise or experience to build the technology infrastructure required.

BaaS has also enabled the birth of embedded finance (the concept of tailoring financial services products at the point of need), which will forever alter the relationship banks have with their customers. At best, it puts the bank at the centre of everything a customer does but at worst, the bank is just a third-party in facilitating a transaction. This creates a unique opportunity for neobanks to insert themselves in the heart of a new value ecosystem but requires strategic partnerships to succeed.

Neobanks 2.0

Retail banking is very local in nature, and aside from a select few megabanks which have global status and presence in multi-geographies – for example, HSBC, Santander, ING Bank, and Standard Bank – retail banking is dominated by a handful of local players.

The market dynamics of neobanks is similar in that no neobank dominates on a global scale – Revolut is closest to doing this in terms of its customer base across multiple geographies/regions – and there is an array of differing strategies across regions of how to succeed as a neobank. Unlike incumbent banks, which provide a broad suite of financial products that are not always accessible via the same digital experience, neobanks start very focused and deliberately provide a narrow offering yet slick user experience which ensures there is increased engagement with the customer.

Many neobanks start with a basic current/checking account and a pre-paid debit card with financial incentives to sign up, for example no fees, cheaper FX rates or cashback offers plus a “waitlist” to drive more signups on the premise of scarcity.

Increasingly, there is a new wave of “neobanks” emerging that not only serve specific needs but are curated for specific communities, including Daylight (banking for the LGBTQ community), Nerve (banking for musicians), 11Onze (banking for Catalonians), Panacea Financial (banking for doctors), and Moonbeam (banking for military veterans).

All of these communities have specific financial needs, whether it’s their preferred name on a bank card or an easier way to collect royalties on music streams. The sense of community and shared valued remains important in banking and presents an opportunity to evolve. Banking is becoming increasingly commoditised and to stay relevant, you need to understand the needs of your target customer and personalise your services for them.

There has been a lot of doom and gloom around the future of neobanks, but as they pass through their teenage years and mature into fully fledged adults, they can co-exist with their elder incumbents and potentially dethrone them if established retail banks think the threat will diminish.

About the author

Philip Benton is a senior fintech analyst at Omdia and writes analysis on the issues driving technological change in financial services. Prior to Omdia, he led consumer trends research in retail and payments at strategic market research firm Euromonitor.

Philip Benton is a senior fintech analyst at Omdia and writes analysis on the issues driving technological change in financial services. Prior to Omdia, he led consumer trends research in retail and payments at strategic market research firm Euromonitor.

In this column, Philip will discuss the technological implications and consumer expectations of the latest fintech trends.

You can find more of Philip’s views on fintech via LinkedIn or follow him on Twitter @bentonfintech.