Open banking: what you need to know

Open banking: an introduction

The landscape for financial services is changing, and the jury is still out on how the endgame is going to play out. However, one of the concepts that is starting to stand out as inevitable is open banking. This development emerges out of a perfect storm of shifting customer behavior, regulatory changes, the threat from digital ecosystems such as Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon (GAFA), and the quest for new business models are driving banks toward open banking.

The coming European Payment Services Directive (PSD2) is requiring banks to open up the payment infrastructure to third-party providers. New business models based on a platform economy is threatening existing revenue streams. As an example, the P2P lending industry is seeing significant growth, especially in developed countries with strong financial markets. In 2015, the alternative finance industry in the US grew to $36.49 billion, a 212% annual increase from the $11.68 billion in 2014. Europe is also catching on, the total European alternative finance market, grew by 92% to reach €5.43 billion in 2015.

There is no need to ask what will be the Uber of banking. The Uber of banking is Uber. 30% of Uber drivers in the US have never had a bank account, but is instead allowing drivers to easily register for a bank account (through integration to a bank partner) or prepaid card when signing up to work for Uber, according to the documents. By doing so, drivers can be paid the same day they work instead of weekly or monthly. Effectively making Uber the fastest growing acquirer of small business accounts in the US.

This shows that industry boundaries are blurred in a digital world. The payment service M-Pesa by Vodaphone and Safaricom has 18 million customers and more than 80 000 agent outlets, financial services account for 9 percent of Telecom operator Telenor’s total revenue in Pakistan. Customer expectations shaped by digital ecosystems differ from the traditional approach to digital marketing where the dominating logic has been to bring customers to the company’s website or proprietary application platform. Citi research refers to this development contextual commerce, where a technology/platform enables a consumer to interact and transact with their chosen merchant/brands in the consumers preferred context or medium.

New technology if shifting the center of gravity for traditional core banking systems. A blockchain-based approach to core banking could act as a catalyst to fracture the monolithic and vertically integrated approach to core banking. A modular approach to lending, syndication, capital markets could utilize blockchain to tie it all together. All the other elements of transactions management, the integrity of transactions, messaging, etc are inherent features of blockchain. Banks cannot afford to ignore the internet of things. When machines are able to perform transactions with machines in real-time at a marginal cost basis, the concept of payments will become obsolete in many use cases as transactions become automated and integrated into other platforms and services. As paying for an Uber today is hidden for the end-customer, the self-driving car of tomorrow could perform payments to the charging station on its own behalf.

These trends all sum up to the inevitability of open banking or banking as a platform.

However, open banking should be perceived as more than just a technical implementation. For banks to embrace open banking, incumbents need to also challenge internal culture and existing business models. Spanish bank BBVA has been a pioneer in this field together with Fidor, and banks like Capital One, ABN Amro and Nordea are all joining the open banking revolution. While open banking may not be the silver bullet for reinventing banking industry, it represents a catalyst for change.

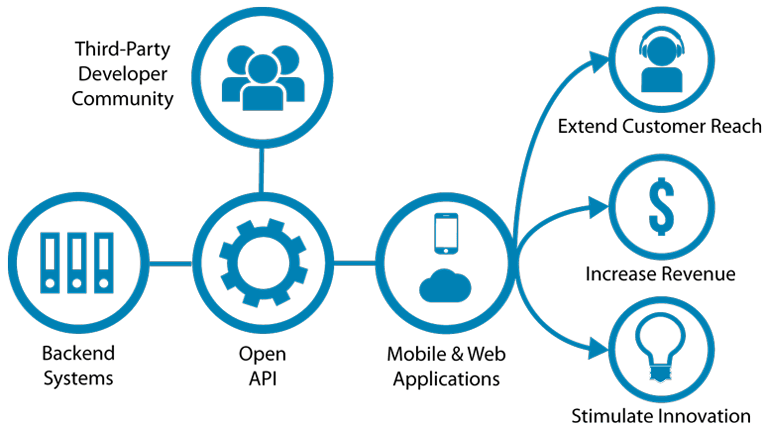

APIs are at the heart of open banking. If executed correctly propose to increase innovation, foster collaboration, extend customer reach and lower costs compared to existing legacy systems. A key concept in the open banking paradigm is to use open source technologies to enable third-party developers to build financial applications on top of the banks’ existing infrastructure. This will most likely spark fears of becoming a commodity and giving away the customer interface for many bankers and may seem like the banks will be relegated to the back seat while third-party technology companies are driving the car.

When I started working in banking, my job was to prevent that from happening. Now I am strongly advocating that if the customer wants it, the back seat is probably the best place for banks as long as it is done willingly. After all, there is a vast difference between choosing to chill out in the back seat and being forced to.

With this, I wish to go more in-depth of the key concepts of open banking in the next series of posts covering various topics related to open banking.

The nature of digital ecosystems

It is impossible to address the subject of open banking without looking at the nature of digital ecosystems. While regulatory changes may act as a catalyst for open banking, the growth and nature of digital ecosystems are in my opinion the primary driving force behind the open banking paradigm.

The banking industry is facing many of the same perils as the telco and media industry has been through in the latter years, and the primary challengers are the same ones that have been feasting at the media and telco’s profit margins for more than a decade. These are the four horsemen of the incumbent’s apocalypse (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon). While they are vastly different in many ways, they all share the traits of a successful digital ecosystem.

Every digital ecosystem starts out as a digital platform, and according to World Economic Forum, the platform economy is expected to disrupt all, or certainly, most existing industrial sectors while stimulating the birth of many new ones. According to Irving Wladawsky-Berger of MIT, a platform or complement strategy differs from a product strategy in that it requires an external ecosystem to generate complementary product or service innovations and build positive feedback between the complements and the platform. The effect is much greater potential for innovation and growth than a single product-oriented firm can generate alone. Scale increases the value of a digital ecosystem, helping it attract more complementary offerings, which in turn brings in more users and increase the value of the ecosystem. A successful digital ecosystem manages to repeat this process.

Napster may have challenged the status quo for the record industry, but it was neither the .mp3 file-format nor the iPod that disrupted the physical music distribution. It was when Apple created a seamless digital ecosystem for digital music consumption through iTunes things started to change. However, as the world progress, yesterday’s innovations become today’s museum pieces, and streaming is already rendering digital music download obsolete. So far, Spotify is excelling at this game, and one of the reasons is their ability to utilise big data analytics and social connections to create a unique personalised listening experience. The ability to create collaborative playlists and connect with your friends through Facebook gives Spotify a competitive advantage over competing services by leveraging third party access to Facebooks digital ecosystem.

Facebook stands out as one of the foremost examples of a well-executed digital ecosystem. Starting out as a social network, Facebook has evolved to a digital ecosystem and something similar to an operating system for your digital identity. Facebook has probably realised this a long time ago and allows a fragmentation of the front-end by leaving both Instagram and WhatsApp as separate applications. When it comes to user engagement, Facebook’s reigns supreme above all others. WhatsApp has exceeded 1 billion users, and Facebook Messenger also reports more than a billion users, handling 60 billion messages a day combined — three times the number of traditional text messages. The result is a separation of Facebook messenger from the Facebook content platform as a separate platform

A digital ecosystems horizontal integration should also include both customers, partners and third-party services. Facebook caters to brands and agencies that wish to take advantage of Facebook’s vast user penetration though Atlas and Pages Manager.

At the same time, Facebook allows third-party developers to create apps and services through Facebook for developers for the Facebook content platform as well as encouraging everyone to create third-party apps as chatbots on the messenger platform. Allowing co-creation and open innovation, while ensuring data collection through Facebook Connect.

Amazon recently updated their API Gateway service to include Usage Plans. Usage Plans allow Amazon API Gateway customers to regulate and monetise their own APIs through different levels of access and different categories of users. In addition, Amazon also opened up Alexa’s APIs.

An important trait by successful digital ecosystems is their ability to cater to third parties as well as platform owners. Had it not been for the existence of such ubiquitous platforms as Android and iOS as well as Google Maps for its core functionality in addition to Google Play and Apple’s App Store for distribution it is difficult to imagine how Pokémon Go could have achieved the scale and success we witnessed earlier this year.

A successful digital ecosystem is often based on a core engine or business model. However, as the external environment is changing, so has the center of gravity for digital ecosystems pivoted accordingly?

iTunes reigned supreme as the center of Apple’s ecosystem, but the iPhone required another core engine. This transition birthed the app store as the new core in Apple’s digital ecosystem. Google has gone through the same evolution from AdWords and AdSense to the Android platform with Google Play as the center for third party engagement. Amazon has also successfully pivoted from the traditional marketplace as core to Amazon Web Services, which is now Amazon’s most profitable segment. Facebook is still rooted in the user’s digital identity, however, acknowledging shifting user behavior and increasing focus on the messenger platform.

When facing disruptive innovations, digital ecosystems are powerful offensive tools. It was not the iPhone who killed Nokia, it was the app store. In the age of digital ecosystems, it is important to find one’s position. I strongly discourage attempting to be Google if you are not Google.

Introduction to APIs

To fully grasp the business potential of open banking, it is useful to have some insights into the technical concepts defining the open banking paradigm. This is meant to be a short introduction to APIs for non-technical people. There are over 12,000 APIs offered by firms today, according to programmableweb. Salesforce.com generates 50% of its revenue through APIs; Expedia.com generates 90%, and eBay, 60%.

An API is in its simplest form a standardised protocol for computer programs to talk to each other and is integral to modern software development. The use of APIs range from web-based APIs, operating systems, databases, hardware, or software libraries.

An API specifies the connection mechanism, the data, and functionality that are made available and what rules other pieces of software need to follow to interact with this data and functionality. Although have been used to link software components within an organisation along, the Internet has given rise to the popularity of external web-based or public APIs. An organisation can use a public API to allow third parties to access their data or services in a controlled environment. Using an API means that only desired aspects of software functionality are exposed, while the rest of the application remains protected. A Facebook “like” on a third party website and an embedded YouTube video are typical examples of the use of public APIs.

In addition to the examples mentioned above, companies such as Google, Apple and Facebook have created their digital ecosystems through the use of public APIs. BY allowing third parties to add functionality to their core offering, these companies become platforms for third-party innovation. Besides driving revenue, it also shortens time to market through crowdsourcing and co-creation of new products and services, as well as service customer, needs through customer demand-driven development.

EBA has made a useful overview of the contents of common technical standards in today’s APIs:

Data Transmission: the way the data is transmitted securely. Almost all APIs use HTTP/HTTPS as a transport layer because it is simple and widely compatible, although there are APIs, which can be used over a wider variety of transport protocols.

Data Exchange: the format of the exchanged data. The most common formats are XML and JSON. While XML has slightly more functionality than JSON, the latter is winning in popularity. JSON can be used for most purposes and is less detailed, thus allows for faster exchange and is considered better machine-readable. Some companies offer their APIs in both formats, whilst others only have one format available.

Data Access: access management (who gets access to which data and how is this achieved). There are multiple standards for this; popular ones are SAML and OAuth 2.0. The first is an XML-based framework and is widely used in business-to-business interfacing. OAuth is a framework that originated in the consumer web services world.

API Design: the way APIs are designed. Common standardised design principles for APIs are REST (Representational State Transfer) and SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol). REST is currently more popular due to its focus on solving issues related to performance, scalability, modifiability, portability, and reliability. Although SOAP is still popular in enterprise environments, it is considered more complex to implement.

APIs allow technology to evolve exponentially and each company to focus on its own developments, integrating whichever services or data it lacks through the most appropriate API supplier in each case. As an example, about 75% of mobile apps resort to some type of internal API to offer information or features to its users.

When it comes to APIs, the level of openness determines potential reach.

- Private APIs

Private APIs are closed APIs, and therefore exclusively accessible by parties within the boundaries of the organisation. By definition, these are not considered “Open APIs” in this information paper.

- Partner APIs

APIs that are open to selected partners based on bilateral agreements. Like Private APIs, Partner APIs are exclusively accessible at the discretion of the provider of the APIs. Bilateral agreements on specific data exchanges between for instance a bank and an enterprise resource planning (ERP) software provider is an example of a Partner API.

- Member APIs

This type of API is open to everyone who is a formal member of a community with a well-defined set of membership rules. When becoming a member of such a community the API provider allows access to the community members who comply with community membership rules and regulations. Future PSD2-mandated Account Information and Payment Initiation Services fall into this category as only authorised or registered Third Party Providers (TPPs) can obtain access.

- Acquaintance APIs

This type of Open APIs is inclusive, as they are open to every- one complying with a predefined set of requirements. Developer portals distribute this type of API, which also comes with some form of standardised agreements. Merchant access to point-of-sale (POS) APIs is an example in this category.

- Public APIs

Public APIs are inclusive and can thus be accessed by anyone, typically with some form of registration for identification and authentication purposes.

As software continues its march to transform all industries, lack of connectivity increasingly equates to being broken. If software developers are the new rock stars, then APIs are the instruments.

Getting the business model right

APIs are at the heart of open banking. If executed correctly propose to increase innovation, foster collaboration, extend customer reach and lower costs compared to existing legacy systems. A key concept in the open banking paradigm is to enable third-party developers to build financial applications on top of the banks’ existing infrastructure. To succeed with an open banking strategy without rendering oneself obsolete, finding the right business model is imperative.

For banks considering opening their infrastructure, an API strategy should be considered a business strategy, not an IT strategy. Giving away API access free may drive brand loyalty and allow the API provider to enter new channels, but may prove unsustainable over time. If executed properly, free API access may act as a stepping-stone for both direct and indirect business models.

Data exchange is one of the most common API models and is the core of Facebook’s Graph API. For banks pursuing a databased business model, the rule of thumb is to create a two-way data feed where you receive data every time third parties consume the API.

Transaction-based models are perhaps the most familiar one for banks, and does not differ much from traditional transaction banking services. The main difference in an API context is the way companies like PayPal and Stripe allows third parties to integrate and utilise their services through plug and play APIs, thus reaching out to a broader audience and driving payment volumes.

Charge by call is the most straightforward monetization model, where third parties pay each time a service offered through the API is called. To succeed with this model, your services need to offer a clear value proposition. Before setting up direct monetization models, you should talk to your customers to see if they would be willing to pay for these services and for how much. As an example, the default price per API query for IBM Watson is $0.0025.

Subscription-based pricing for API access could both be fixed or dynamic. A fixed model is straightforward and offers full API access for a fixed monthly cost. A pay as you go approach is more dynamic, where pricing is determined by metered usage. For example, a cloud computing platform’s usage price could be determined by the operating system platform and size of a platform on an hourly basis. Another dynamic subscription model is a tiered model. Developers sign up for and pay for a particular usage tier based on the number API calls over a fixed time. While the cost increases per tier the cost per API, call usually drops. Vertical Resources uses the tiered business model. Prices drop with consuming more volume (API calls), so after analyzing usage over a period, users can adjust their tier.

Freemium is a great way to get started for both API owners and third parties curious to connect and explore and could serve as a stepping-stone towards both subscription-based models as well as charge by API call. In this, model companies offer developers some of their APIs capabilities free and then charge for additional functionality. For example, a web mapping service could allow a low number of calls to be made to the API free and then any additional calls to the API are charged. Adding additional API access to a Premium subscription offers a strong motivator to upgrade to a higher package, as it allows end users to customise their experience and workflow more easily.

Balance sheet is an important strategic resource for banks opening their APIs to third parties. Many fintechs are seeking bank partners to provide core financial infrastructure for new products and services. This could benefit banks by increasing assets under management, providing deposits for capital requirements as well as the potential for additional interest margins if credit is involved.

Revenue sharing is an option to encourage open innovation and co-creation with third parties. In this model, it is often the third party who is paid based on the popularity of the third party application. A revenue sharing model offers shared incentives for both API owner and third-party community and should also provide additional scaling incentives.

No matter which model you choose, it all comes down to profitability. One way to measure, the success of your APIs is a simple Average Revenue Per User Model (ARPU) in order to see if an API strategy is worth your while. Finally, yet importantly, the business model must be aligned with the long-term vision and strategic agenda.

A playbook for banks and fintechs

After looking into the subject, it is becoming clear that there is no one size fits all open banking strategy. Rather, several tactical moves are being played out by a variety of both banks and fintechs. To conclude this guide to open banking, I will attempt to describe some of the widely applied moves, as well as give some examples of the type of players that are conducting these moves.

Move #1 The API marketplace

Becoming a fintech app store is for many banks the preferred alternative to open but, but still maintain control over customer relationship and customer data.

BBVA pioneered this move through their API marketplace and has seen several followers. Nordea recently announced that they would launch a fully functioning developer portal and community hub as the first iteration of their open banking strategy. The move makes Nordea one of the first movers in the Nordics to openly state their Open Banking vision. This is not limited to big banks, as Starling is launching an API marketplace of their own. Starling’s public API enables third parties to access customer data and build on top of the Starling Platform to create products and services such as chatbots, spending analytics, or connections with the Internet of Things (IoT).

Move #2 The account aggregators

The ability to create a unified overview of your bank accounts is for many ones of the key strategic possibilities under the XS2A rule in PSD2. This move need no further elaboration, as we already see examples of players like Swedish fintech-startup Tink attempting to gain an early position through “screen scraping” prior to PSD2. In order to succeed in this game, a contextually relevant user experience is crucial, and merely presenting aggregated account balances in a retrospective fashion will not make the cut.

As the directive is implemented, this is likely to become the new normal for every online and mobile banking service out there, effectively shifting focus for banks from attempting to be your customer’s main or only bank towards attempting to be your customer’s favorite bank.

Move #3 The independent advisor

Building on the account aggregator, the trusted financial advisor also includes data from other sources such as rewards and loyalty points, utility bills, insurance, total cost of car ownership. The ability to give a holistic view of everyday finances will further strengthen the customer relationship.

Op Financial Group in Finland is following this strategy, and has launched an electric car leasing service. Players seeking to follow this move should also be prepared to include competing products and services from competitors if these are the best solutions for the customer in order to build and maintain trust.

Move #4 Cross-industry collaboration

Hana Financial and SK Telecom in South Korea has formed a joint venture with the goal of developing a mobile financial services platform. The joint venture is aiming to combine SK Telecom’s mobile technologies and big data analytics with Hana Financial Group’s experience in financial products and mobile financial services to build an open fintech ecosystem. When launched, the platform will offer a variety of mobile financial services – such as payments, remittance and asset management through a single mobile app.

Norwegian banks and Telenor previously attempted to collaborate on the mobile payment platform Valyou, as well as Polish bank mBank has launched a mobile banking services directed at SMEs in collaboration with Orange.

Move #5 Hackathons/crowdsourcing

Opening up and allowing approved third parties to build innovative solutions on top of various banks APIs has become a popular choice to test the waters before moving towards the open banking deep end. However, hackathons can also be used beyond simple exploration.

ICICI Bank in India is now hosting their second season of their “appathon”. The mobile app development initiative offers access of over 250 diverse APIs from both ICICI Bank, IBM Bluemix, VISA and National Payments Council of India to the participants. The programme aims to create the next generation of banking applications on mobile and web space by attracting developers, technology companies, start-ups, technopreneurs and students across the globe.

Move #6 Bank/fintech collaboration

Almost every open banking initiative has some element for fintech/bank collaboration. To distinguish this as a separate move, I am specifically addressing bilateral collaboration efforts between one single bank and one fintech.

The Financial Brand has provided some good examples of how BBVA and Dollar collaborate on payments; USAA collaborates with Coinbase to include cryptocurrencies in their product offerings. Here in the Nordics, the latest development is a collaboration between Nordea and fintech-startup Spiff, which aims to make savings fun and easy.

Move #7 Banking as a service

For many incumbent banks, the idea of becoming a wholesale provider of commodity utilities is considered a worst-case scenario. However, this is absolutely a viable strategic option for some. Germany-based Solaris Bank was the first to provide a fully licensed banking platform aimed at fintechs. The platform offers payments, transaction services, deposit and credit services, as well as compliance and KYC/AML solutions.

Privatbank in Ukraine is offering a similar service through the Corezoid process engine. Railsbank in the UK is another banking as a service player that provides fintech companies a range of wholesale banking services, including IBANs, receiving money, sending money, converting money, direct debit, issuing cards, and managing credit through APIs.

Move #8 The white label product vendor

Similar to providing the whole bank as a service, some banks and fintechs have collaborated up with the bank as a silent white label provider of products and services that often require a banking license to deliver.

Notable examples include Webbank in Utah issuing loans for P2P lenders like LendingClub and Prosper as well as providing lines of credit for Paypal. As a result, Webbank was able to generate a return on equity of 44 percent based on a profit base of only $15,5 million. CBW Bank was also an unknown bank out of Kansas before it was known as the initial bank partner for Moven.

Move #9 Openness at the core

In order to build an open, digital bank, legacy core banking systems are often pointed out as one of the key obstacles. These systems are closed and monolithic by nature, while open banking requires openness and real-time processing. However, Thought Machine is building their core banking solution on a blockchain-style technology that is said to be ideal for interfacing with open banks. Temenos has also established a marketplace in order to connect fintech providers to financial institutions using Temenos banking software.

No matter which strategic option(s) you choose to follow, open banking will fundamentally change banking the same way internet banking once did. As banks become integrated parts of digital ecosystems, the distribution of banking products will change and in the end become more valuable in the right context for the end customer.

By Christoffer O. Hernæs, chief digital officer, S-Banken

Read his blog here.

Did you know Afterbanks?

Thanks for this extremely informative article. I especially enjoyed the comment about the API strategy being a Business Strategy. As more of a business person working in IT, I constantly have to remind folks that without a business need or use case, technology is just that! Too often these decisions are made solely by architects or engineers.