Managing the risks of blockchain

Good judgement is the result of experience and experience the result of bad judgement.

Mark Twain

Introduction

The potential benefits of blockchain are widely discussed and advertised! Yet, because there is no return without risk, this article will provide an analytical framework for evaluating the risks inherent in the use of blockchain in financial services institutions.

We put forward two simple, yet significant, propositions.

- Make sure that business problems are your main driver and technology is the supporting tool, rather than the other way around.

- Thoroughly analyse and understand the associated risks upfront in order to minimise the costs and potential downsides of implementation. The ultimate decision is not a question of finding the perfect solution, but rather one where the benefits outweigh the drawbacks.

In this article, we assume a basic understanding of distributed ledger technologies (DLT) which incorporate the sequencing of blocks (blockchains). We will therefore not delve deeply into describing what a DLT is and how it works. However, and in order to reduce confusion, we would like to make clear that blockchain and cryptocurrencies (such as Bitcoin) are not the same thing. Bitcoin is based on a distributed ledger technology, but one can have a blockchain that does not involve any cryptocurrencies at all. In other words, Bitcoin is not blockchain, just like email is not the internet.

Analysing the risks

Based on the aforementioned points, we will provide a framework for analysing blockchain related risks, focusing on pre-implementation, implementation and post-implementation.

Pre-implementation risks

Blockchain is often portrayed as the silver bullet for more problems than it is designed to solve. Therefore, the first step in pre-implementation risk analysis is to understand the cases where blockchain could be the right solution to our problem.

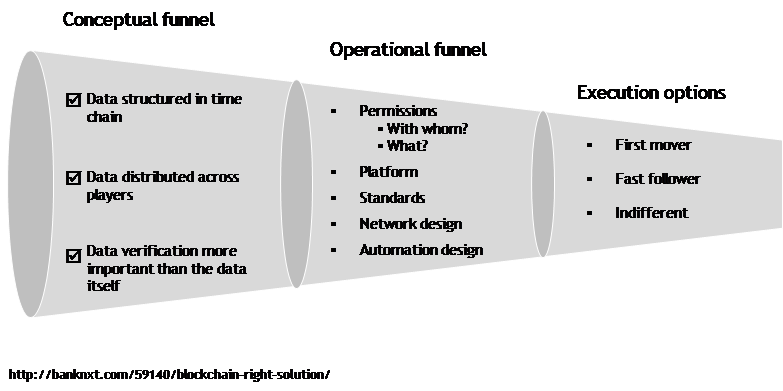

Practically, blockchain has the potential to address several problems, but there are also applications where blockchain is either not effective, or a rather inefficient solution. The following decision funnel can provide the analytical structure for evaluating the applicability of blockchain as a solution to the business problems we are trying to solve.

At the conceptual level, three elements stand out:

- Blockchain timestamps data in a sequential chain

Does the problem you are looking to solve require that the data is primarily structured in a time chain? In other words, is the sequencing of activities the most important dimension of what you are trying to capture?

- The blockchain is about the proof of the data, not necessarily the data itself

Blockchains are designed (and therefore are most efficient) to hold a record of activity. In other words, blockchain architectures should not be understood as databases holding information, but rather as a cryptographically secured proof of the information itself.

- The proof of the data is distributed across a network of participants

Blockchain applications are founded on the sharing of data, and therefore the deployment of such technologies needs to be chosen for business problems where sharing is a benefit more than it is a risk.

Once the conceptual criteria have been satisfied, the next step is to evaluate the benefits and risks of different operational designs. These are the following:

Permissions and sharing. Generally speaking, blockchains can be public, permissioned or private.

- Public (or unrestricted) blockchains are potentially accessible by everyone. They constitute the better understood ‘version’ of blockchain, due to the awareness surrounding Bitcoin, a prime example of a public blockchain.

- Permissioned blockchains are restricted to a number of approved participants. In other words, even though they are not open to everyone, they can be made available to the members of a specific group of participants. The R3 consortium is a good example.

- Private blockchains are used by a single party. They constitute the most extreme version of permissioned blockchains. As we have already discussed, their usefulness is –theoretically at least– limited.

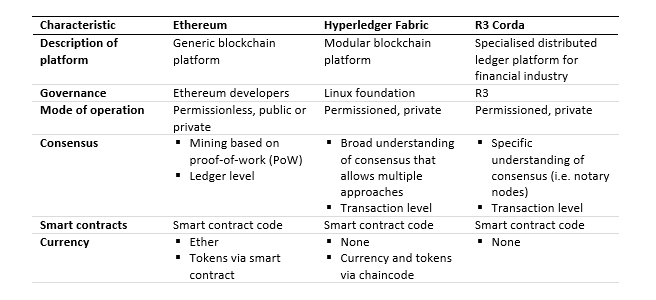

Platform. Related to the discussion above is the choice of platform. The following table, by Philipp Sandner of the Frankfurt School Blockchain Centre provides an excellent summary between the three most commonly referenced blockchain architectures.

Standards and integration / interoperability. Given the early stages of blockchain development, it is only natural that there are no concrete blockchain standards (something like a Blockchain ISO). While the standards are being developed (often by a trial and error approach) within each platform, the interoperability between platforms is extremely limited, if non existent.

Network design. Regardless of the platform, the network design needs careful attention. Are all the nodes equal or can some of them carry greater significance than others? Are forks (competing versions of the ledger) permissible? And so on… Each design decision comes with its own promised benefits and associated risks (known and unknown).

Automation design. Last but not least, DLTs are equipped with a powerful automation technology known as smart contracts. Smart contracts represent a condition-based, self executable layer of code sitting on a blockchain infrastructure. The potential benefits are numerous, but so are the risks. Automated actions can be risky and the ability of humans to intervene should be considered as a mitigating factor.

Implementation risks

Having gone through the pre-implementation funnel, we can be more confident that blockchain is indeed the right solution for the business problems we are trying to address. Once that has taken place, the actual implementation comes with its own risks.

To avoid repeating points that can be deduced from the discussion above, we will focus on a handful of additional ones.

- First, in any environment with several parties involved, implementation can only be as fast as the slowest member. Consensus is required at every step of the way and delays due to the competing priorities of participants inevitable; it is needless to mention the delays due to sheer participant incompetence.

- A second risk are the interfaces with legacy systems. Despite our enthusiasm and the evangelical scripts encountered in mainstream blockchain discourse, blockchains have to integrate with existing systems. No easy task, we are sure you agree.

- Scalability of the solution is another risk. This parameter depends both on the original design as well as the agility of the technology itself. Either point is an unknown at this moment and, as a rule, the more agile the solution the more expensive it is.

- Associated with the above is the overall cost of maintenance. By definition, distributed = more expensive. Bitcoin is a prime example, whereby the computing power and electricity costs of the infrastructure are rising dramatically day by day. Whilst, usually, technology is a means of reducing costs, blockchain scalability may not always benefit from economies of scale. Once again, the more we understand and improve the technology, the more this risk will be mitigated. At this moment, however, it is still early days.

Post implementation risks

The most obvious post implementation risk is cyber risk. It is a lot easier to manage cyber risk on private technological infrastructures, and even there examples of cyber risk abound. Blockchain is by definition a shared infrastructure and the extent of exposure to cyber crime is largely an unknown.

Most cyber risks arise from within, whether due to malice or sheer ignorance. Even if the architecture is robust to attacks from the outside, it may not be to internally generated mistakes. What happens if consensus is achieved on an erroneous entry? Can this error be reversed? What if a mistake in the code has been distributed across the network and rendered ‘immutable’?

Change management post implementation is another obvious risk. In an environment where several participants need to agree on the change, motivating and implementing it can be a lot more challenging than one would have hoped for.

Associated with the discussion above is the process for managing changes. Are maintenance and updates managed by a third-party vendor? Or by the consortium? I am sure you have already been in this situation several times, where vendor availability and skills management are in short supply. Blockchain infrastructures for constantly changing business problems can be one of the biggest challenges you have experienced to date.

Risks beyond our control

It goes without saying that several of the risks that blockchain implementations are likely to face are beyond the control of infrastructure participants.

Regulation is the most obvious example. Regulators are already concerned about the potential impact and associated risks of blockchain and regulatory intervention is not something not to be expected for.

Similarly, what happens in the case where the infrastructure provider folds? In the case of Bitcoin, we have experienced the collapse of Mt. Gox, an exchange which at some point handled around 70% of all Bitcoin transactions worldwide. And, even though Ethereum appears quite stable at this stage, it remains a private company with all the risks that relying on one entails.

Other risks external to our control include the cost of electricity, the cost of technology updates and the potential emergence of competing disrupting technologies, in an environment where technological progress advances in leaps and bounds.

We will not expand on this list as we want to avoid sounding like unlovable Cassandras. Our objective is not to provide an endless catalogue of caveats, but rather the appropriate logical foundations which often seem absent from the surrounding hype. We believe you got our point!

Conclusion

Blockchain architectures have the potential to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of participant operations in financial services. At the same time, these benefits come with several risks, many of which are unknown. Before jumping on the bandwagon, we recommend that a thorough analysis is undertaken, taking into account the framework that we have outlined above.

By Periklis Thivaios

The article was originally published on RiskMinds365 (FinTech Futures’ sister company)