Will regulators make an example of trading unicorn Robinhood?

“Planning is valuable, though the plan is usually useless,” American investor Ben Horowitz once said.

After three major outages in quick succession, US trading app Robinhood might rue now having contingency plans in place, despite the unlikely odds of it ever needing them.

These weren’t just any old outages. The first happened the same day US stocks had one of their best days since the financial crisis, with the Dow Jones experiencing its biggest one-day points gain ever.

On 2, 9 and 12 March, Robinhood’s band of merry men failed to deliver on their promise of gold for all

Robinhood’s ten million users were locked out of trading for the entire day, unable to make any money off the stock market surge.

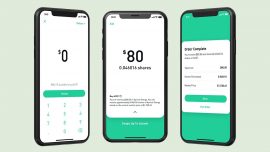

Fintechs founded in the 2010s all set out to tackle financial inclusion. Robinhood was no different, even deciding to carry this particular USP everywhere in its name: to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor.

But on 2, 9 and 12 March, Robinhood’s band of merry men stumbled on their promise of gold for all. The outages were put down to an “unprecedented load” on the fintech’s infrastructure, blaming in part a “record” number of account sign-ups.

In other words, the fintech has grown quickly, and arguably taken on the trust of the masses without responsibly building a platform strong enough to hold them all up.

A Robinhood spokesperson tells FinTech Futures that the firm “proactively emailed” all customers following the outages, encouraging them to get in touch with the trading app with their concerns.

A Plan B?

Mike Taaffe, a Florida-based attorney, is heading up a class action lawsuit against Robinhood on behalf of what he says are now “hundreds” of angry customers calling into his office demanding reimbursements.

“We don’t think they were set up to do it properly,” Taaffe tells FinTech Futures. “I think this will force the various state regulators to consider whether they give licences to companies trading purely online without sufficient back-up.”

The lawsuit requests an injunction for Robinhood to install a more robust system. This is what most of the complaint leans on, namely the fintech’s supposed lack of redundancy-based architecture.

Part of the litigation will include a discovery phase, where Robinhood itself will be investigated. “If we find out they knew and didn’t do anything, then we will pursue punitive damages,” says Taaffe.

This would require Robinhood to pay a fine on top of compensatory damages. But what will be interesting to follow is how prior knowledge is defined in the case.

The question is if Robinhood knew its platform could only endure a certain level of stress, and was aware the systems could fail under certain conditions, would that be enough to qualify it to pay for damages?

Asked about what the app’s tech stack looks like, a Robinhood spokesperson said it does have redundancy in place for some of its “critical transaction flows and infrastructure”.

“The load we’re encountering these days due to factors including, among others, highly volatile and historic market conditions, record volume, and record account sign-ups is unprecedented, so we’re investing more in this area,” they said, adding that the team were already working on improvements when the outages happened.

The lawsuit is exploring unchartered waters

Perils of digital-only

Taaffe says “the fact it’s purely a tech-based platform and that there’s no individual to contact” is what “makes this case very different.”

In 2018, Robinhood’s co-founder Baiju Bhatt told TechCrunch: “Brick-and-mortar locations are costly. Our goal with this product was to build a completely digital experience so we can reduce our overhead so we can pass more of the value back to customers.”

Whilst being digital-only might have made operations cheaper in the short-term, in the long-term it may have affected Robinhood’s reputation among the trading community.

Asked about the lack of human financial advisers, Robinhood’s spokesperson tells FinTech Futures that “this is communicated to customers when they sign up”.

As for its customer service team, the app said: “Unfortunately, we experienced unusually high volumes of customer inquiries during the outage, but we’ve worked as quickly as possible to respond.”

Taaffe hopes more regulations are put in place for online-only security trading following these outages. As part of a new wave of digital-only trading, Robinhood is one of the first to do it on such a big scale for ordinary people.

The fintech may also have to notify the UK’s FCA of its outage

This means the lawsuit is exploring unchartered waters and could perceivably lead to a watershed moment for online-only trading, where US regulators such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) take actions which force fintechs like Robinhood to match their customer growth with equivalent technology investment.

How will UK regulators respond?

But whilst Robinhood’s services are currently focused in the US, the fintech did also land a UK licence last year to start trading overseas.

FinTech Futures asked UK law firm Harper James’ financial services solicitor John Pauley what Robinhood’s outages will mean for its impending launch to British consumers.

As well as the “significant financial loss in payouts” and subsequent regulator action it could face in the US, Pauley says the fintech may also have to notify the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) of its outage if it hasn’t done so already.

FCA-regulated firms like Robinhood have a duty to notify it of “matters having a serious regulatory impact” such as “a significant adverse impact on the firm’s reputation”, which Pauley argues can be seen in the US outages.

“While we do not know for sure, it seems likely that Robinhood’s intention would be to use the same systems in the UK that they use in the US so there is a potential that such issues may happen in the UK when they go live here,” Pauley explains.

Asked what technology it will be using in the UK, Robinhood tells FinTech Futures that infrastructure improvements are “a top priority” in the run-up to its UK launch as well as its ongoing US operations.

If Robinhood does notify the FCA, then the UK regulator would have to review it and consider whether or not to take further action.

Pauley also notes that FCA-regulated firms are required to commence activity within 12 months of being granted a licence. Robinhood secured its licence on 7 August 2019, so if it doesn’t kick off its UK launch by 6 August this year, it could risk having its authorisation withdrawn all together.

Robinhood’s investors and customers have poured roughly $900 million into the fintech

What next?

As well as the class action lawsuit filed in Florida, traders have also filed complaints with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (Finra).

Now it’s a case of waiting. As Taaffe says, the Florida lawsuit needs to finish its discovery phase before the class action case can develop further, and if Robinhood has officially notified the FCA of its US outages, then the FCA will be reviewing it right now.

In the UK, regulators have already begun to build out their stance when it comes to outages in the banking sector. In December, the Bank of England, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) said the firms “are expected to take ownership of their operational resilience and that they will need to prioritise plans and investment choices based on their impacts on the public interest.”

This means no blaming third-party technology companies. Robinhood is not technically a banking firm, so will not be held under these rules, and its technology is all in-house. Still, could we see electronic trading firms met with similar regulatory actions as the service becomes further widespread?

Currently electronic trading is growing, both as a way to financially include the masses, but also as a popular alternative for major stock exchanges. Perhaps as major incumbent trading houses face online issues, regulators will take more notice.

As for Robinhood’s legal team, it can currently refer customers to its platform agreement which explicitly states that it is not liable for “temporary interruptions in service due to maintenance, website or app changes, or failures”.

This sort of fine print will inevitably be a cause for major contention throughout the Florida case, as lawyers such as Taaffe bring into question its ethics, and how much “failure” it can cover before liability comes into play.